Clues about the occult foundations of American Healthcare from India and Scandinavia

The use of the caduceus of Hermes as a symbol of the medical profession was the subject of Dr. Walter Friedlander’s book “The Golden Wand of Medicine.” You can read my summary of Dr. Friedlander’s book in Hermes Trismegistus and American Healthcare. Friedlander posed many questions about the use of this symbol and its adoption in the United States in 1917. Today, runaway healthcare costs and inaccessibility of medical care have revived interest in the caduceus of Hermes, the liar, thief and trickster god. Who is Hermes, and does his caduceus form the occult foundations of American healthcare?

Friedlander focused mainly on Hermes in Greek mythology but there are echoes of this deity in other parts of the world. Additional clues about the nature of Hermes are provided by Edward Moor’s “The Hindu Pantheon” and Georges Dumézil’s “The Stakes of the Warrior.” These accounts give strength to Dr. Friedlander’s identification of the caduceus of Hermes as a malevolent influence. We begin by identifying deities similar to Hermes in The Hindu Pantheon by Edward Moor.

Nareda

One of the points Friedlander made in his book is that it is not known why the Greeks chose to associate Hermes with the Egyptian Thoth, who has a very different personality. Moor’s description of the Hindu deity Nareda provides the answer. According to Moor, Nareda or Narada is a key figure connecting the Hindu scriptures to Hermes. Narada has many of the characteristics of Thoth. He is “a wise legislator [and] great in arms, arts, and eloquence;” he is also an astronomer, and a musician. He invented the Vina, a sort of lute…and was a frequent messenger of the gods. In these and other points he resembles Hermes, or Mercury. Some think he is the same with Thoth.

In the Hindu Pantheon, Nareda is one of the ten lords of living beings. In the Sivpuran, which contains the doctrines of the worshipers of Siva, Nareda was born from Brahma’s thigh. However he is also said to be the offspring of both Brahma and Saraswati. He was one of the seven Rishis.

The histories of Krishna often introduce Nareda. They say he is only another form of Krishna himself…Crishna (in the Gita, p. 82) speaks of his ‘holy servants, the Brahmans and the Rajarshis.’ He says, ‘I am Brigu among the Maharshis…and of all the Devarshis I am Narad.’ (P. 80)

Buddha and Woden

According to Friedlander, there are five main historical accounts of Hermes. In the classical period the Homeric version of Hermes changed to become associated with inventing, buying and selling. This was probably the influence of Rome and resulted in the Greek Hermes becoming associated with Mercury.

In Moor’s Hindu Pantheon, Buddha has been said to share the same character with Mercury. So has the Gothic Woden. Each gives his name to the same planet, and to the same day of the week: Budhvar, in India, is the same with Dies Mercurii, or Woden’s day–our Wednesday. Buddha, Booda, Butta, and others are mere varieties, in different parts of India…and so ‘perhaps is the Bud, or Wud, of the ancient pagan Arabs. Pout in Siam; Pott, or Poti, in Tibet; and But, in Cochin China, are the same.’

Noah

It was mentioned in American Cosmology and Arlington National Cemetery that many of America’s founders were believers in the doctrines of Hermes Trismegistus and that when he was discredited as an historical figure, he was replaced by Noah. In the Hindu pantheon, the seventh Menu was Vaivaswata, or child of the sun. He is the one saved on the ark and therefore the father of the whole human race. The seven Rishis were said to be with him on the ark, although they are not mentioned as fathers of human families. However, it is also said that Vaivaswata’s “daughter Ila was married…to the first Buddha, or Mercury, the son of Chandra, or the Moon, a male deity, whose father was Atri, son of Brahma.” Because of this, Vaivaswata’s posterity are divided into two branches called the Children of the Sun, from (Vivaswat, the Sun) his own father; and the Children of the Moon, from the parent of his daughter’s husband. One of Vaivaswata’s other names is Satyavrata, whom Sir William Jones thinks corresponds to the Italian Saturn.

Aesculapius, Hermes and Parvati

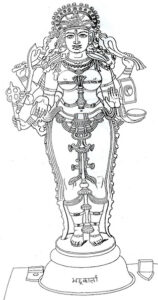

In Hinduism, Parvati is the sacti or energy of Siva. She has many additional names, the most common aside from Parvati are Bhavani, Durga, Kali, and Devi, or the Goddess. Ma is a name of Bhavani in her personification of nature, and under the name of Bhavani she represents the “general power of fecundity.” She has connections both to Aesculapius and to Hermes.

According to Moor, “The word Cala, or Kala, signifying black, means also, from its root, Kal, devouring: whence it is applied to Time, and, in both senses in the feminine, to the goddess in her destructive capacity. In her character of Mahacali she has many other epithets, all implying different shades of black or dark azure: viz. Cali, or Cala, Nila, Asista, Shyama, or Shyamala, Mekara, Anjanabha, and Krishna.”

Wilford said that the river Kali, the Nile in Egypt, got its name from Mahacali, who, according to the Puranas, made her first appearance on its banks in the character of Rajarajeswari, also called Isani, or Isi. That river is also called Nahushi, from the warrior and conqueror Deva Nahusha, or Deonaush, who Wilford thought was probably the Dionysius of the ancient Europeans. Dionysius is often portrayed with similar characteristics to Nareda and Krishna. (Some writers have suggested that Dionysius was a Minoan deity–I think the fact that he was born from Zeus’ thigh makes that doubtful, but more on that later.)

Sir William Jones thought that in her character of Bhavani, she was “Venus presiding over generation, and for that reason was sometimes portrayed as having both sexes. He refers to her bearded statue at Rome, the images called Herma-thena, and in those figures of her which had a conical shape.” (Hermes is also said to be a hermaphrodite)

In her form called Bhadra-Kali, Maha-Kali, and by other names, she is eight-handed, ashta-buja. In one image of her one of her right hands holds something like the caduceus of Hermes, without snakes.

Friedlander said that the caduceus of Hermes was originally topped by a figure-eight with the top open.

On the other hand, Mahacali also has the names of Amba, or Uma; and Aranyadevi, or goddess of the forest. She is Prabha, meaning light; and Aswini, a mare, the first of the lunar mansions. It is said, “In this shape, the Sun approached her in the form of a horse, and, on their nostrils touching, she instantly conceived the twins. Her twins are called Aswini-Kumari, the two sons of Aswini.” They are beings of importance in the identity of Aesculapius. The house cock is one of the Goddess’s symbols; Friedlander said the house cock was a symbol of Aesculapius.

Surya and Esculapius

(Moor’s spelling)

It is believed that Surya, (the Sun) descended frequently from his car in a human shape, and left a race on earth. They are equally renowned in the Indian stories with the Heliades of Greece. His two sons, called Aswina, or Aswini-Cumara together, are considered twin brothers, and painted like Castor and Pollux. But they have each the character of Esculapius among the gods. The story says they were born of a nymph, who, in the form of a mare, was impregnated with sunbeams.” (Jones. Asiatic researches, Vol. I. p. 263.) Esculapius’s symbol is not identical to the caduceus of Hermes. He carries a rod with a single snake. Many consider it a more appropriate symbol for a healer.

Fourteen Gems and the Beverage of Immortality

There is a Escuapius-like figure among the Hindus, who had a different sort of birth. In the notes on page 342 Moor says, “…I do not recollect that Dhanwantara, the Esculapius of the Hindus, has an attendant serpent like his brother of Greece. The health-bestowing Dhanwantara arose from the sea when churned for the beverage of immortality. He is generally represented as a venerable man, with a book in his hand.” He was a physician and was also one of the fourteen gems obtained when the ocean was churned for the recovery of Amrita, the beverage of immortality.

The Caduceus of Hermes Gets Wings

Friedlander said the staff of Aesculapius had snakes by the 5th century BC, wings by the 1st century AD, and snakes and wings together by the 15th or 16th century. There is a picture in Moor’s plates of Krishna with a winged figure, who Moor thought was his divine spouse Rukmeny. Moor calls this picture ‘singular’. He seems to be saying that the caduceus of Hermes may have developed from the staff of Aesculapius.

Woden/Odin, as characterized by Georges Dumézil

If the caduceus of Hermes symbolizes the occult foundations of American healthcare, and if this symbol is associated with the Hindu deity Siva, Scandinavian mythology describes the nature of these influences. The connection with Odin, or rather the relationship between Odin and Thor on the one hand, and Siva/Rudra and Vishnu on the other, is discussed by Georges Dumézil in “The Stakes of the Warrior,” where Kṛṣṇa represents Viṣṇu as his avatara.

Dumézil presents legends from Scandinavia and India, which have similar patterns and themes, and discusses the comparison first in terms of his theory of the three functions, where Odin and Thor represent the magical sovereign, and the champion or warrior, the “first and second entries on the canonical list of the gods of the three functions.” The problem, he attempts to solve, is this: Although the elements of the stories are too similar to be coincidence, in the Rg Veda, Rudra (Mahadeva or Siva) and Viṣṇu don’t fit, individually or together, in the trifunctional structure. He says the Vedic Viṣṇu is an associate of Indra at the second level (warrior) and although he is above Rudra in the hierarchy, he doesn’t fit in the first level, or that of magical sovereign, and the two of them, Rudra and Viṣṇu don’t interact. It was Hinduism that later gave them trifunctional characteristics. (Actually, Dumézil says the Indian gods still do not have a definite trifunctional aspect, although Hinduism put Viṣṇu and Rudra in a more oppositional relationship.) Further, Rudra operates more on the third level as a healer and herbalist, and on the second level only as archer, alone or in his plural form Rudrāh. Also there are problems with fitting Odin and Thor into the trifunctional structure in the Scandinavian legend.

In fact, in the tales of the Scandinavian Starkaṑr and the Indian Śiśupāla, there seem to be strong similarities between Odin and Rudra, even though, hierarchically speaking, the similarities should be between Odin and Viṣṇu. Both Odin and Rudra have a weakness for the demonic, and in the end, must be rescued or have things put right again, in Odin’s case by Thor, and in Rudra’s by Viṣṇu (or Kṛṣṇa).

Others, besides Dumézil have listed physical and mental traits of character and behavior shared by these two seemingly different deities, Odin and Rudra.

Both are tireless wanderers, they like to appear to men only in disguise, unrecognizable, Odin with a hat pulled down to his eyes, Rudra with his uṡniṡa falling over his face; Odin is the master of the runes as Rudra is kavi; and above all the bands of Rudra’s devotees, bound by a vow, endowed with powers and privileges recall sometimes the berserkir, sometimes the einherjar of Odin. This sovereign god, this magician, unarguably has one of his bases in the mysterious region where the savage borders on the civilized. Like Rudra-Śiva he is often, in terms of ordinary rules, even immoral…Like Rudra-Śiva, he has his taste for human sacrifice, particularly the self-sacrifice of his votaries. More generally, like Rudra-Śiva, he has in him something almost demonic: his friendship and weakness for Loki are well known; but Loki is the malicious rogue who, one fine day, in arranging the murder of Baldr, takes on the dimensions of a ‘spirit of evil,’ of the greatest evil.

By contrast, Thor, like Viṣṇu, exterminates demons, or giants (although he is also sometimes aided by Loki or Thjalfi). According to Dumézil, the “overriding difference” between the pairs of Odin-Thor and Rudra-Viṣṇu is that “Viṣṇu–in the only sense that matters here–is superior to Rudra-Śiva, even constituting his ultimate recourse, while Odin, notwithstanding his impudences with the giants, is superior to Thor, hierarchically speaking and apparently also in the degree of esteem accorded him by human society. His complexity, his magical knowledge, the post-humous happiness he assures his followers in Valhöll, all make him theologically more interesting.”

For these reasons, Dumézil categorizes Odin and Rudra-Śiva as the “dark gods,” and Thor and Viṣṇu as the “light gods…Each of the two heroes, the Scandinavian Starkaṑr and the Indian Śiśupāla, belongs entirely to the dark god and is opposed by the light god. But the structures are almost reversed by the fact that in Scandinavia the dark god holds the first place, being more important in this life and especially in that to come, and that consequently his favor is the more desirable, the light god having only an immediate and limited range; whereas in the Indian legend it is the light god who is in the spotlight and directs the game, and whose favor in this life and in the hereafter is most fervently sought, while the dark god acts only implicitly, without showing himself, through the “Rudraic” nature of the hero.” Dumézil concludes that the Scandinavian hero, the favorite of Odin, is the good hero, while the Indian hero, a type of Rudra-Śiva, is the evil one, apparently because of the hierarchical superiority of Odin, or his function as magical sovereign.

The Question of Incarnation

According to Moor, only the Gokalast’has adore Krishna as the Deity; other sects of Hindus condemn him. “The anathematizing of Krishna is not confined to the Buddhists, but is common to other sects of Hindus equally hostile to his claims to deification.”

It is told in the Puranas how:

Krishna fought eighteen bloody battles with Deva-Cala-Yavana, or Deo-Calyun, from which the Greeks made Deucalion.” Deo-Calyun was a powerful prince who lived in the western parts of India. In the Puranas he is called an incarnate demon because he resisted Krishna’s ambitions, almost defeating him. However, Krishna was victorious in the eighteenth battle through treachery.

The title of Deva is not of course given to Calyun in the Puranas, but would probably have been given him by his descendants and followers, and by the numerous tribes of Hindus, who, to this day, call Krishna an impious wretch, a merciless tyrant, an implacable and most rancorous enemy; in short, those Hindus who consider Krishna as an incarnate demon, now expiating his crimes in the fiery dungeons of the lowest hell…

See Also:

Sources:

Dumézil, Georges. “The Stakes of the Warrior”. University of California Press Berkeley. 1983

Moor, Edward. “The Hindu Pantheon”. T. Bensley. London, 1810.

Scholem, Gershom. “On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead”. Schocken Books Inc. New York. 1991

Pictures from Moor’s “Hindu Pantheon”:

Mahadeva as Ardha Nari: Plate 24, figure 1

Bhadra Kālī and Caduceus: Plate 28

Rādhā, Krishna, and attendant Gopia: Plate 67

Crishna nursed by Dēvakī: Plate 59