Today people either look forward to the New Age or they fear it. Religious believers are probably the largest group of people who fear the age of Aquarius. They may not believe that an age has real influence on the world, but they fear New Age belief systems and alternative lifestyles. It’s important that we all understand the connection between the birth of Aquarius and human civilization.

(more…)Tag: Siva

-

Adam, Noah and the Snake-king

In a previous article it was pointed out that the words ‘Man’ and ‘Woman’ in the second chapter of Genesis were translated from īš and ‘iššă. This led to two assumptions:

The first man and woman of Genesis 2 were deities.

These deities were Siva and Parvati, who is also Osiris and Isis.īš and ‘iššă

There is evidence that īš and ‘iššă have the general meaning of ‘Lord’. Following are two examples provided by Edward Moor:

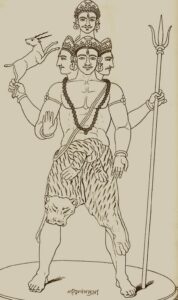

“When they consider the divine power exerted in creating, they call the deity Brahma, in the masculine gender also; and when they view him in the light of destroyer or rather changer of forms, they give him a thousand names: of which, Siva, Isa, or Iswara, Rudra, Hara, Sambhu, Mahadeva, or Mahesa, are the most common…

“Mahesa is maha, great, and Isa, Lord; the epithet is prefixed to many names of gods…”

Swayambhuva

The Hindu Adam, Swayambhuva, is called ‘the first of men’, but he is clearly something more than human.

“Swayambhuva, or the son of the self-existing, was the first Manu, and the father of mankind: his consort’s name was Satarupa. In the second Veda the Supreme Being (Brahm) is introduced in this way: ‘From me Brahma was born: he is above all; he is pitama, or the father of all men: he is Aja and Swayambhu, or self-existing.’ From him proceeded Swayambhuva, who is the first menu: they call him Adima (or the first, or Protogonus): he is the first of men; and Parama-Parusha, or the first male. His help-mate, Pracriti, is called also Satarupa: she is Adima, (the feminine gender) or the first: she is Visva-Jenni, or the mother of the world: she is Iva, or like I, the female energy of nature; or she is a form of, or descended from, I: she is Para, or the greatest: both are like Mahadeva, and his Sacti (the female energy of nature), whose names are also Isa and Isi. ((Moor, Edward, F.R.S.. “The Hindu Pantheon”. T. Bensley, London. 1810))

Siva and Parvati

In The Hindu Pantheon īš and ‘iššă are more strongly associated with Siva and Parvati. And Moor associates Siva/Parvati with the Egyptian goddess Isis. Because Hinduism is fundamentally monotheistic, many deities who have their own attributes melt into each other and become one. It is also true that each of the deities has a consort, but the consorts can be reduced to one as well.

The Goddesses

The goddesses, in turn, are merely the female energy or ‘sacti’ of their lord. For this reason, the Supreme Being of any particular sect, whether it is Vishnu, Siva or Brahma, is said to be a hermaphrodite, with male and female attributes combined. So it is not really clear in what way the mythology should be applied to human men and women.

The Effects of Doctrine on Women

For Christians, the doctrine of original sin is at least partly responsible for policies concerning women, but that doctrine is not a universal belief. Judaism and Islam have no such doctrine, but they have all proscribed the rights and equality of women to some degree. This is particularly true of Islam. So there seems to be a common tendency that aligns with the conception of woman as portrayed in the story of the Fall of Man, and which is independent of the doctrine of Original Sin. It could be argued that a rationale for subjection is the main function of the story of the Fall of Man. But on the other hand, maybe it is the attempt to say in mythological language what really happened. We just don’t happen to understand the language.

Control Over Animals

There are similarities in the creation stories of many cultures between Noah and Adam. For example, Noah and Adam both had control over animals, as did the Chinese Shang-te, the Hindu Siva, and the Greek Hermes. Additional shared elements include the ark and the dove.

In Chinese mythology, the Yin, or darkness, or the female principle is the ovum mundi and becomes the Earth, the ark or the Great Mother. Heaven, or Shang-te is the son of Earth, (or the ark), as he is ‘born’ from her womb. But he is also the builder of the ark, and the creator of Mother Earth. So she is his daughter. And since they are both born from the same circle, they are brother and sister. Heaven or Shang-te marries his mother or daughter or sister. In other words, their union is incestuous.

Androgyny

Since Eve was created from Adam’s rib they are brother and sister, or father and daughter. This is true of the Greek Jupiter and Juno and of the Hindu gods, as well. “Brahma, the Supreme Being of Hinduism, is an androgynous conjunction of Adam and Eve, the universal parents of the human race.” 1

The Snake

It is interesting that Chinese, Hindu and Greek myths also identify the snake with both Adam and Noah. The woman seems to be connected indirectly. Ancient legends say that in the golden age there was no distinction of sex. According to Plato, “in the first arrangement ordained by Jupiter there were neither human politics, nor the appropriation of wives and children, but all lived in common upon the exuberant productions of the earth.” It was the hero-god, also called the snake-king, who instituted marriage.

Marriage

In Greek mythology marriage was instituted by Cecrops. Cecrops was a native of Egypt, who led a colony to Athens about 1556 B.C. He was a culture hero who introduced the worship of Zeus Hypatos, and forbade the sacrifice of living things. His marriage decree came about in this way:

“He was arbitrator at the ‘strife’ of Athena and Poseidon. The women, who exceeded the men by one, voted for Athena, and to appease the wrath of Poseidon they were henceforth disenfranchised and their children were no longer to be called by their mother’s name. The women’s decision came as a shock to old Cecrops and he forthwith instituted patriarchal marriage.”

All of the hero-gods of Greece were serpents.

“Cecrops is a snake, Erichthonios (Cecrops’ son) is a snake, the old snake-king is succeeded by a new snake-king…What the myths of Cecrops and Erichthonios tell us is that, for some reason or another, each and every traditional Athenian king was regarded as being also in some sense a snake.”

Cecrops Harrison thinks this came about because of the ceremonial carrying of snakes or figures of snakes. This was like the carrying of phalloi, a fertility charm. A Hermes of wood was the votive-offering of Cecrops, and it was possibly snake-shaped. 2

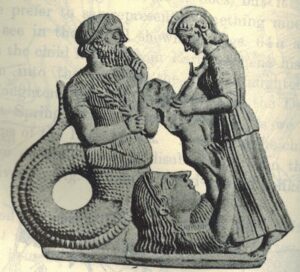

In Chinese mythology, the dragon is the symbol of Shang-te. In this way, the Chinese gods resemble the fish-gods Vishnu and Dagon. The serpent was the symbol of the transmigrating diluvian god, who was reborn. It was also the token of regeneration for those initiated into the mysteries.

Siva and His Coat of Skin

Shang-te also gave the first couple coats of skins and instituted marriage. In Hinduism, Siva is depicted with a coat of skins.

Siva and His Coat of Skin Demon-god, Hero-god, and snake-king are the terms used by Christian missionaries in the Chinese Recorder. In that publication, these names referred to non-Christian myths. But according to the same publication, Shang-te’s dragon is identical with the serpent in the Garden of Eden. However, in the bibical story, it was God Yahweh who provided coats of skin and instituted pariarchal marriage. Patriarchal marriage is clearly implied in the following verse:

“I will make intense your pangs in childbearing.

In pain shall you bear children;

Yet your urge shall be for your husband,

And he shall be your master.” (Genesis 3:16)In the notes on verse 16 concerning ‘pangs in childbearing’ we are told that this is a parade example of hendiadys in Hebrew. The literal rendering would read “your pangs and your childbearing,” but the idiomatic significance is “your pangs that result from your pregnancy.”3

And the sentence Yahweh pronounced on the serpent becomes more interesting as well.

God said to the serpent:

I will plant enmity between you and the woman,

And between your offspring and hers;

They shall strike at your head,

And you shall strike at their heel. (Genesis 3:15)It seems the serpent who became the mortal enemy of the woman and her offspring (perhaps in their human character) was the serpent-king. Both male and female are affected. The verse says “the woman and her offspring”.

The Chinese Myth and the Old Testament

In a strict comparison with the Chinese myth, the serpent-king would be God Yahweh and also his son, Adam/Noah. (According to the Anchor Bible, the deity in the Garden of Eden was “God Yahweh” rather than “Yahweh”. This may be the personal name of a different deity.)

It seems that these myths refer to a political development that has adverse consequences for the woman and her offspring.

Lot and Noah

Lot’s connection with Noah in this passage is explained by the fact that Lot was saved from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, which he believed had destroyed the whole world. He also had incestuous relations with his daughters. Something similar may have happened between Noah and his son Ham. This is the pattern of a snake king.

In the Chinese Recorder,

“This Demon-god or First Man or Noah is a reappearance of Adam in his deified character…or ‘Imperial Heaven’, and also the Son of Noah as being the eldest of the triplication Fuh-he, Shin-nang, Hwang-te; or Shem, Ham, and Japhet…. ‘Noah, in every mythological system of the pagans was confounded, or rather identified with one of his three sons. Fab. Vol. I. p. 343. Vishnu (one of the triplication of Bram or Monad) appears distinct from Menu (First Man) and personates the Supreme Being: yet, single, he is certainly Noah or Menu himself: as one of a triad of gods springing from a fourth still older deity (the Monad, or elder Noah) he is a son of Noah. Ibid. vol. II. 117. Considered then as Noah, we find Jupiter (the elder Monad or Chaos) both esteemed the father of the three most ancient Cabiri (Cælus, Terra, and First Man), and himself also reckoned the first of the two primitive Cabiri (Cælus and Terra); Bacchus being associated with him as the younger. This however is a mere reduplication, for Jupiter and Bacchus are the same person. &c., i. e. the First Man.”

-

The Warrior and His Gods

In “The Stakes of the Warrior” Georges Dumézil uses his theory of the tri-functional structure of Indo-European society as a framework for the analyses of stories belonging to three different areas of the world; India, Scandinavia, and Greece. His comparative study includes the Scandinavian saga of Starkaṓr, the Indian tale of Śiśupāla, and the Greek story of Herakles. ((Dumézil, Georges. The Stakes of the Warrior. Translated by David Weeks. Ed. With introduction by Jaan Puhvel, University of CA Press, Berkeley, LA, London. 1983)) In each story, the warrior sins and his gods demand sacrifice. This study was cited in Hermes in India and it will be used again in subsequent posts, so I would like to summarize it here.

In each story the hero sins against each of the three Indo-European functions–the functions of the sovereign, the warrior, and fertility or sexuality. In the process he fails in the very duties and responsibilities that give his life meaning. An important element in each story is the rivalry of two deities who take an interest in the life of the hero, and are directly or indirectly responsible for his crimes.

Starkaṓr/Starcatherus and Odin

For the Scandinavian tale of Starkaṓr there are two sources. One is the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus (1150–after 1216). The other is the Gautrekssage, which is a redaction of the poem, the Vikarsbálkr, from the 13th or 14th century. The saga also adds additional material from ancient sources. Saxo calls the hero Starcatherus; the saga calls him Starkaṓr.

Starkaṓr/Starcatherus is either a giant, or he has giant ancestry. In the saga, his grandfather was a giant but he has a human form. In Saxo he is born with extra arms and Thor prunes them off, giving him a human appearance. The child begins life under the patronage of Othinus or Odin, but also under the hostile and watchful eye of Thor, who hates giants in general, and according to the saga, Starkaṓr in particular.

As Starkaṓr’s story begins, the fathers of little Starkaṓr and Vikar are killed in battle. The boys are brought up together among the people of Herthjófr, king of Hördaland. One of Herthjófr’s men, Hrosshársgrani raises Starkaṓr. Hrosshársgrani is Odin in disguise, and the god has dark designs on him. Although he is supposed to be Starkaṓr’s protector, he has decided that Starkaṓr will be the one to bring him Vikar, king of Norway and Starkaṓr’s childhood friend, as a sacrifice.

After living for nine years with Hrosshársgrani, Starkaṓr helps Vikar reconquer his realm, and accompanies him on many victorious expeditions. During a Viking expedition Vikar’s fleet is “becalmed” near a small island. The king and his crew have a “magical consultation” and determine that Odin wants a man of the army to be sacrificed by hanging. They draw lots and the king is chosen. After this shocking development they postpone deliberations until the next day.

In the meantime Hrosshársgrani acts. He wakes Starkaṓr and takes him to the Island and through a forest. In a clearing they come upon a strange assembly.

“A crowd of beings of human appearance are gathered around twelve high seats, eleven of which are already occupied by the chief gods. Revealing himself for who he is, Odin ascends the twelfth seat and announces that the order of business is the determination of the fate of Starkaṓr…The event comes down to a magical-oratorical duel between Odin and Thor.”

Thor hates Starkaṓr because his grandfather was a giant. He hates him even more because his grandfather, long ago, abducted a young girl. When Thor rescued her he found that she actually preferred the giant over the “Thor of the Æsir”! This was Starkaṓr’s grandmother. In consequence of this lasting grudge, Thor imposes Starkaṓr’s first curse before the council of the gods, “Starkaṓr will have no children.”

Odin compensates for this curse. “Starkaṓr will have three human life spans.”

It continues in this way, the gods taking turns.

Thor says “He will commit a villainy in each.”

Odin answers, “He will always have the best arms and the best raiments.”

Thor: “He will have neither land nor real property.”

Odin: “He will have fine furnishings.”

Thor: “He will never feel he has enough.”

Odin: “He will have success and victory in every combat.”

Thor: “He will receive a grave wound in every combat.”

Odin: “He will have the gift of poetry and improvisation.”

Thor: “He will forget all he has composed.”

Odin: “He will appeal to the well-born and the great.”

Thor: “He will be despised by the common folk.”

As they return to the ship, Odin informs Starkaṓr that he must pay for the assistance he has just received by sending him the king, or in other words, by putting Vikar in a position to be sacrificed. Odin will take care of the rest. Starkaṓr is apparently convinced that he must pay and he agrees to help Odin. The pact between the warrior and his gods has already decided Starkaṓr’s fate.

The next day Starkaṓr suggests to the king that they carry out a mock sacrifice and Vikar agrees. Starkaṓr bends down the limb of a tree and fastens a noose to it and also around Vikar’s neck. Then Starkaṓr takes a magic reed-stick given him by Odin and thrusts it at the king saying, “Now I give thee to Odin.” Then he releases the branch. The reed-stick becomes a spear and pierces the king. The branch springs up and drags the king into the leaves, where he dies.

Starkaðr and the murder of King Víkar “From this deed Starkaṓr became much despised by the people and was exiled from Hördaland.”

Now we depend on Saxo’s version. Starcatherus still has a long career ahead of him and he accomplishes many admirable exploits, but after the death in battle of another master, a Swedish king, he shamefully flees from the battlefield, allowing the army to be defeated. After this debacle, he joins an army of Danish vikings and eventually serves the Danish king, Frotho, where he is a “model of martial virtue”.

For his third sin he allows conspirators to bribe him and he kills another master, the Danish king Olo. He has already sinned against his duty to kings and his duty as a warrior. In taking a bribe for the murder of Olo he sins against the morality of the third function–not through sexuality but through greed.

The hero has been aging during his three life spans but he keeps all of his strength until after the third crime. Finally old age, his many wounds, and his crimes burden him to the point where he wishes for his own death. He doesn’t want to die shamefully of old age so he looks for a warrior who will give him an honorable death. Providentially he meets Hatherus, the son of one of the conspirators in the murder of Olo. He confesses that he is the one who killed Hatherus’ father, (Starcatherus killed all of the conspirators). Hatherus agrees to behead him in exchange for the money that Starcatherus received for killing Olo. Starcatherus also wishes to give Hatherus his invulnerability and tells him to stand between his head and his body after his death. In a moment of suspicion, however, Hatherus stands back and does not accept this gift.

Śiśupāla and Kṛṣṇa

Dumézil acknowledges that there are problems posed by the character of Kṛṣṇa in the Mahabharata. He thinks that what is said about him is a transposition of the myth of an ancient Viṣṇu, like that which produced the Pandavas from an archaic list of the functional gods. But for this study it is enough that the relationship of Kṛṣṇa/Viṣṇu is stated in the episode. It provides structure comparable to the tale of Starkaṓr/Starcatherus.

The story of Śiśupāla is not central to the cosmic conflict in the Mahabharata. And while Starcatherus, aside from his three crimes, was a perfect example of a defender of kingship, as well as a warrior and a teacher, the Indian hero is said to be the reincarnation of a demon that Viṣṇu has already killed twice in past lives. We learn of his previous lives after he challenges the proceedings of Yudhisthira’s sacrificial ceremony. This information, and the story of the hero’s birth, provide the justification for his hostility to Kṛṣṇa.

Śiśupāla was born into the royal family of the Cedis. He had three eyes and four arms and he uttered inarticulate cries like an animal. His parents had decided to expose him, but they heard a disembodied voice saying that this was not the “Time” for the child’s death. His slayer “by the sword” has been born, lord of men.

His mother demands to know “who shall be the death of this son!”

The voice answers,

“He upon whose lap his two extra arms will both fall on the ground like five-headed snakes and that third eye in the middle of the child’s forehead will sink away as he looks at him–he shall be his death.”

These things happen as soon as the child is placed on Kṛṣṇa lap. Śiśupāla’s mother witnesses the fulfillment of the prophecy and is fearful for her son. She asks Kṛṣṇa to forgive the “dereliction of Śiśupāla”.

(Because of Śiśupāla’s physical similarities to Rudra/Śiva, and also because of his name, which is said to be a transposition of paśupati or lord of animals, this story is similar to the story of Starkaṓr/Starcatherus in its conflict between two divinities, in this case Rudra/Śiva and Kṛṣṇa/Viṣṇu.)

Kṛṣṇa promises that he will forgive one hundred offenses, even though they may be capital offenses. But by the time Śiśupāla challenges the proceedings of Yudhisthira’s sacrificial ceremony he has exhausted his one hundred offenses. His tirade against Krṣṇa is the one hundred and first offense. However, only five offenses are listed. Dumézil argues that the list can be further reduced to three. The five sins, which Kṛṣṇa recited to the kings assembled at Yudhisthira’s ceremony are:

1. “Knowing that we had gone to the city of Prāgjyotiṣa, this fiend, who is our cousin, burned down Dvārakā, kings.”

2. “While the barons of the Bhojas were at play on Mount Raivataka, he slew and captured them, then returned to his city.”

3. “Malevolently, he stole the horse that was set free at the Horse Sacrifice and surrounded by guards to disrupt my father’s sacrifice.”

4. “When she was journeying to the country of the Sauvīras to be given in marriage, the misguided fool abducted the unwilling wife-to-be of the glorious Babhru.”

5. “Hiding beneath his wizardry, the fiendish offender of his uncle abducted Bhadrā of Viśāla, the intended bride of the Karūṣa!’The offenses are distributed as follows: The first and second offenses are committed against the warrior function; the third offense, against sovereignty; and the forth and fifth offenses have to do with sexuality. However, all of the sins are directed against the king. The similarity of the first and last two offenses indicate that the list may have been inflated, and that originally there were only three sins.

Kṛṣṇa continues,

“For the sake of my father’s sister I have endured very great suffering; but fortunately now this is taking place in the presence of all the kings. For you are now witnesses of the all-surpassing offense against me; learn also now the offenses he has perpetrated against me in concealment.”

Śiśupāla does not relent. He continues to scold those who honor Kṛṣṇa, who is “no king”. Finally Kṛṣṇa throws his discus, cutting off Śiśupāla’s head. A sublime radiance rises from the “body of the king of the Cedis, which, great king, was like the sun rising up from the sky; and that radiance greeted lotus-eyed Kṛṣṇa, honored by the world, and entered him, O king…”

Krsna cuts off Sisupala’s head There is no mention of corresponding consequences after each of Śiśupāla’s sins and he does not offer himself for death as Starcatherus did. Also another king, Jarāsandha, is mentioned, although he has no part in the story itself. Śiśupāla, although a king in his own right, is said to be Jarāsandha’s general, giving him the same position as Starcatherus, who served kings but was not himself a king. Jarāsandha is accused of holding Kṛṣṇa’s clan in jail, with plans to sacrifice them. In other words, he was under contract to Rudra/Śiva, just as Starkaṓr/Starcatherus was under contract to Odin. This provides another correspondence between the Scandinavian and Indian stories. However, in the Indian version human sacrifice is not as believable as it is in the Scandinavian tales. Also Śiva has no particular interest in kings, as Odin does. This only makes the Indo-European framework of both stories more apparent.

Herakles and his gods, Hera, and Athena

In the Greek story of Herakles, genders are reversed–the rival deities, Hera and Athena, are female. Dumézil makes an interesting observation–the rival deities in the first two stories answer to no superior judge or authority. But in the tale of Herakles, the patriarchal Zeus is given the final word.

Herakles’ birth is told by Diodorus Siculus (iv, 9, 2-3). When Herakles was born he was not monstrous or demonic but he had a certain excess. He was the son of Zeus and Alkmene. Zeus had taken the appearance of Alkmene’s husband, Amphitryon, in order to beget an exceptional king who would rule over the descendants of Perseus. But when Hera learned of his plans she was jealous. She caused the labor pains of Alkmene to slow down and the result was that another heir, Eurystheus, was born first. Zeus then decreed that Herakles would serve Eurystheus and perform twelve labors. In this way he would earn immortality.

Alkmene abandoned her baby out of fear of Hera. Athena and Hera found him, and Athena gave him to Hera who began to nurse him. This saved his life. However he bit her and she pushed him away. Dumézil suggests that this is like the story of Śiśupāla, whose deformities disappeared at the touch of the very god who was destined to kill him. Hera is the sovereign whose first concern is to exclude Alkmene’s son from royalty and demote him to a champion. Athena is the warrior and becomes Herakles’ most trusted friend. The patronage of Athena and the enmity of Hera are a constant theme in Herakles’ life. As for his attitude to the two higher functions, the kingship and the labors, (or fights) he does not attempt to replace the king. He serves him and is sometimes rewarded, but his first sin actually involves his hesitation over entering the king’s service. Starkaṓr/Staratherus serves kings ostentatiously. Śiśupāla is a king who voluntarily serves as a general of another king.

For his hesitation in obeying Zeus and entering the service of Eurystheus Hera strikes him with madness, causing him to kill his own children. He is consigned by Eurystheus to perform twelve labors as well as additional sub-labors.

His next sin is the killing of an enemy by a shameful trick, rather than in fair combat. For this sin he contracts a physical disease. At this point he has no choice but to become a slave of Omphale, Queen of Lydia.

The penalties are not cumulative with Herakles and he is cured of them each time, until the last one. After a new series of “free” deeds he forgets that he has just married Deianeira, and he takes another lover. Deianeira sends him a cloak that she thinks contains a love potion. However, it contains the poisoned blood of Nessos and it gives Herakles an incurable burn. Two of his companions consult the oracle at Delphi in his behalf and Apollo tells them,

“Let Herakles be taken up to Mount Oeta in all his warrior gear, and let a pyre be erected next to him; for the rest, Zeus will provide.”

When all is made ready, Herakles voluntarily climbs onto the pyre and asks each one who comes up to him to light it. No one but Philoktetes has the courage to light the pyre, and Herakles gives him his bow and arrows. Immediately after Philoktetes lights the pyre “lightening also fell from the heavens and it was wholly consumed.”

Hercules burning himself on the pyre But later the arrows caused the death of Philoktetes.

Summary

The strongest similarities are between Greece and Scandinavia.

1. The divinities who oppose each other over Herakles and Starkaṓr are those of the 1st and 2nd functions. The ones in India (Krṣṇa/Viṣṇu and Rudra/Śiva) don’t fit in the tri-functional structure but they compare to Odin and Thor in other aspects.

2. Herakles is reconciled after his death with the sovereign Hera, wife of Zeus. The one who benefits from the death of Starkaṓr is Höṑr, (Hatherus) who is close to Odin, (the sovereign, and dark god comparable to Śiva). Śiśupāla is reconciled with Krṩṇa/Viṣṇu.

3. Herakles and Starkaṓr are similar in their basic nature. Herakles has no demonic component and Starkaṓr is made human. But Śiśupāla remains demonic and Sivaistic. Neither Herakles nor Starkaṓr provoke the deity who persecutes them. Śiśupāla does however, although Krṣṇa does not persecute him.

4. Herakles and Starkaṓr are more interesting than the deities, but Śiśupāla is just an incorrigible Indian Loki in the career of Krṣṇa. The reader is on the side of Starkaṓr and Herakles, and also on the side of Athena, but only as Herakles’ helper. The Indian story is more complementary to Krṣṇa/Viṣṇu, and against Śiśupāla.

5. The deaths of Herakles and Starkaṓr are good and serene. That of Śiśupāla is the result of a “frenzied delirium”.

6. A young man is asked to kill the hero in the stories of Herakles and Starkaṓr–but not in the story of Śiśupāla.

7. In the stories of Herakles and Starkaṓr the gift or payment is ambiguous. The arrows kill Philoktetes and Hatherus chooses not to receive the essence of Starkaṓr.

8. The types of Herakles and Starkaṓr are the same, a wandering hero, redresser of wrongs, given to toil

9. Both are educators.

10. Both are poets.

But other similarities tie India and Scandinavia together, in contrast to Greece.

1. Śiśupāla and Starkaṓr are born with deformities. Heracles is not.

2. The Indian and Scandinavian legends make much of a royal ideology. The Greek legend outlines the opposition of Erystheus and Herakles but does not dwell on it.

3. The faults of Śiśupāla and Starkaṓr are foreordained. Śiśupāla’s fate is decided by his demonic ancestry. Starkaṓr’s is decided by lots.

4. Given that Jarāsandha completes the legend of Śiśupāla, India and Scandinavia both charge the heros with the human sacrifice of kings. The Greek legend does not.

5. Starkaṓr and Śiśupāla are both beheaded. Heracles is burned.

6. The deities in the stories of Starkaṓr and Śiśupāla have no higher judge. Krṣṇa/Viṣṇu and Rudra/Śiva don’t answer to Brahma, for example. The divinities in the Greek story are supervised by Zeus.

There aren’t as many similarities between Greece and India, but the failings of Śiśupāla and Herakles are similar in that:

1. The first sin offended a god in the case of Herakles who resisted the command of Zeus; and a sacrificer in the case of Śiśupāla who stole the king’s sacrificial horse. In Starkaṓr’s case his failing resulted from an excess of submissiveness towards a god.

2. The second sin in the case of Śiśupāla and Herakles involves the unworthy betrayal of a warrior. For Starkaṓr it was a shameful flight on the battlefield.

3. Śiśupāla and Herakles have no particular prejudice against the sensuous aspect of the third function, but Starkaṓr, who is ruled by Odin and Thor, condemns this kind of weakness.

-

The Lord of Creatures

In Hermes in India a discussion began about the Lord of Creatures. It is now obvious that this subject is more difficult than I imagined. There are several related terms that have to do with the nature of God. They have similar meanings, but they can belong to completely different gods.

Dumézil said the name paśupati (Lord of Animals) might be the name of the demon who opposed Kṛṣṇa–the demon’s name was Śiśupāla, but it might be a ‘transposition’ of Paśupati. According to a Wikipedia article, paśupati is Sanskrit for Pashupati. This is one of the names of Siva. Definitions differ, but some say it means the Lord of all Created Beings. Here Śiśupāla is associated with Siva.

The name given in the Hindu Pantheon is Prajapati and it belongs to Brahma. It means the Lord of Creatures, or Lord of all Created Beings. Prajapati can also refer to the three major deities together–Vishnu, Siva and Brahma. It seemed reasonable to associate paśupati with Prajapati–both terms denote lordship over animals. Also Śiśupāla possessed a ‘sublime radiance’ which passed to Kṛṣṇa.

In The Names of God another term entered the discussion by way of a new translation of the Book of Job. It was argued that the god who spoke out of the whirlwind was not the sky-god that we normally associate with the Old Testament but a Master of Animals–he was a deity equally concerned with humans and animals–a Paleolithic, hunter-gatherer Master of Animals. This idea led to more research on the archaeological evidence for this deity. The name of Hermes is prominent in discussions about the Master of Animals.

The next set of clues comes from a legend told in “The Hindu Pantheon” and has to do with the nature of the war described in the Puranas. It is said that the conflict arose between the worshipers of the female principle and the worshipers of the male principle. It was “a battle of cosmic proportions” in which the earth lords resisted the rise of a sky god. The war started in India and spread all over the world. It was discussed by Wilford in “Egypt and the Nile”, and repeated by Moor, and also by Christian missionaries in a publication called the Chinese Recorder. Versions differ, but the theme is the same. This was the basis of Grecian mythology with its battles between the gods led by Jupiter; and the giants or sons of the earth. The gods led by Jupiter were the followers of Iswara, worshipers of the sky-god. The giants were the men produced by Prit’hivi, a power or form of Vishnu, (see more on this below) who acknowledged no other deities than Water and Earth.

This conflict is to blame for the rise of theological and physiological contests, veiled by the use of allegories and symbols. Wilford offers the following example of allegorical mythology: “On the banks of the Nile, Osiris was torn in pieces; and on those of the Ganges, the limbs of his consort, Isi, or Sati, were scattered over the world, giving names to the places where they fell…In the Sanskrit book, entitled Maha Kala Sanhita, we find the Grecian story concerning the wanderings of Bacchus; for Iswara, having been mutilated through the imprecations of some offended Munis, rambled over the whole earth bewailing his misfortune: while Isi wandered also through the world, singing mournful ditties in a state of distraction.”

The Servarasa is more specific and says that the conflict involved Siva and Parvati:

When Sati, after the close of her existence as the daughter of Dacsha, sprang again to life in the character of Parvati, or Mountain-born, she was reunited in marriage to Mahadeva. This divine pair had once a dispute on the comparative influence of sexes in producing animated beings; and each resolved, by mutual agreement, to create apart a new race of men. The race produced by Mahadeva was very numerous, and devoted themselves exclusively to the worship of the male deity; but their intellects were dull, their bodies feeble, their limbs distorted, and their complexions of different hues. Parvati had at the same time created a multitude of human beings, who adored the female power only; and were all well shaped, with sweet aspects and fine complexions. A furious contest ensued between the two races, and the Lingajas (worshipers of Siva) were defeated in battle. But Mahadeva, enraged against the Yonijas (worshipers of Parvati), would have destroyed them with the fire of his eye, if Parvati had not interposed, and appeased him: but he would spare them only on condition that they should instantly quit the country, to return no more. And from the Yoni, which they adored as the sole cause of their existence, they were named Yavanas.

The declared victors of the contest differ depending on the storyteller’s point of view. Wilford thought this version must have been written by the Yonyancitas, or votaries of Devi because the Lingancitas say that Siva’s offspring were the most beautiful. The most numerous sect of Hindus are those who attempt to reconcile them, saying that both principles are necessary, and so the navel of Vishnu is worshipped as identical with the sacred Yoni. But it is important to mention, in light of our interest in the Lord of Creatures, that Brahma is ignored.

Brahma was the creator. In the Hindu solar religion, he represents one aspect of the Sun and corresponds to the early part of the day, from sunrise until noon. His realm is the earth, and fire. However, in Hinduism Brahma is not as familiar a figure as Siva and Vishnu, or even mentioned as much as the incarnations and lesser deities. The reason given in “The Hindu Pantheon” is that the act of creation is past. The creator has no further role in the “continuance or cessation of material existence, or, in other words, with the preservation or destruction of the universe.” Now this is the basic premise of Deism. Deism was the religion of the Enlightenment.

Siva, on the other hand, in his aspect of the destroyer, is said to have a sort of “unity of character” with Brahma, although they are usually found in hostile opposition. It is said that destruction is inevitable. It is actually another form of creation.

As mentioned in American Civil Religion and the Enlightenment one of the criticisms of the Enlightenment is that Reason has replaced God. However, it seems that Reason is not just an abstract principle; Reason is a god. In The Hindu Pantheon Reason is an attribute of Nareda.

If Brahma is Prajapati and Śiśupāla is paśupati, Śiśupāla must have been associated with Brahma, not Siva. If the Grecian giants are part of the same conflict, they should also have been associated with Brahma, not Vishnu. So it shouldn’t be surprising that Śiśupāla is not a solar figure. In the Mahabharata, the would-be king whom Kṛṣṇa supported forced Śiśupāla and his fellow kings to attend a sacrificial ceremony where he claimed for himself universal kingship. The original kings were to be his subjects and accept a subordinate relationship to him. During the ceremony Kṛṣṇa was honored all out of proportion to the kings, and Śiśupāla objected. The highest honor being given to Kṛṣṇa was not appropriate, he said, in the presence of “great spirited earth lords”.