Can democrats criticize the Enlightenment? In Harold Kaplan’s analysis of modern literature, he doesn’t criticize the Enlightenment (late 17th to early 19th century), but he mentions it as a timeframe for a modern state of mind which has been detrimental to western thought.1 He doesn’t criticize the Enlightenment in Democratic Humanism and American Literature either.2 He mentions it rarely, for example when he mentions that Melville’s ‘insights deserted the confident ideas of the Enlightenment’. Kaplan is a democrat. His analysis of Democratic humanism analyzes how well the writers of American classics defended democracy.

(more…)Category: Foundations

Unspoken questions wind their way through the national conversation. Where are we going? What can we expect in the future? Will we survive? How can we prepare? Anxiety is increased by omens in the sky and the weather. In myth and religion we hope to find promises and instructions. We hope to rediscover our foundations. But we also find lamentations. We are not children who deny the possibility of destruction and death. Not now. The worst is already upon us. We’ve seen families swept away in the flood and burned in the fire. Let’s face the future like wise men and women. Let’s sit down together like elders of the tribe. Let’s mourn what is lost and love what remains.

-

Religion Must Guide the Political Moment

The religions that are most liable for the current political crisis are Judaism and Christianity. Some may find fault with this statement. They will say religions are irrelevant; today politics are part of a secular world. This is in spite of the fact that the religions of Judaism and Christianity prop up the far Right’s nationalist aspirations. Alternatively, the religious will say that their particular religion is on the side of righteousness. In this view, everyone who disagrees with them, meaning the secular world, is evil.

(more…) -

Modern Israel is Anti-West

In this article, I hope to correct the way progressives think about modern Israel. I think much of our secular sympathy for Jewish people comes from the fact that the Nazi regime hated them and persecuted them. In retrospect, we had that in common with the Jews: the Nazis hated the West as well. But Israel has more in common with war-time Germany than it does with the West. Modern Israel is anti-West. In short, progressives seem stuck on the political contradictions of Israel. Christians give the Jews an additional benefit of the doubt because Christianity and Judaism are kin, religiously speaking.

The West is Israel’s Biggest Victim

Sometimes this preference for modern Israel takes the form of a belief. We believe that the Israeli government’s atrocities are aberrations from Israel’s ideal nature. I will argue on the contrary that Israel’s behavior is the result of her true nature. To put it plainly, modern Israel does not now and never has possessed an ideal nature separate from its atrocities. Worse, Western countries are not simple bystanders to Israel’s actions. The West may be powerful enablers of Israel’s drama, but The West is also Israel’s biggest victim.

Israel and the West Against Hamas Where Does the Far Right End and Israel Begin?

Where doest the Far Right End and Israel Begin? To the United States, the German far right’s critique of the West, seems completely unique to World War II. But Israel hijacked our thinking. According to Rabbi Simon Jacobson of Chabad, Israel opposes the West as much as Germany ever did. For that matter, Israel opposes the entire world. Why? Modern Israel has a race theory that rivals that of the Nazis. Richard Rothschild calls Chabad’s race theory Modern, ‘Moral,’ Reactionary Jewish Racism. This racism does not admit political causes of the strife in Palestine.

Similar to the Netanyahu government’s dependence on the Old Testament story of Amalek, Rabbi Jacobson argues that the conflict in the Middle East started not with rivalry over the land, but with Jacob and Esau. Israel and Palestine are at war because they are descended from two archetypes. It’s a clash of civilizations.

A Clash of Archetypes/Civilizations

Rebecca, the mother of Jacob and Esau, was told she had two nations within her. Jacob was the father of the jewish people and Esau represented Western Roman Christianity. They remain at odds. Their immediate ancestors, Ishmael and Isaac, were not at peace either. Therefore, it’s not a surprise at all in Jacobson’s telling that their children and grandchildren are still enemies.

Strangely, after explaining how the line of Jacob is superior to the line of Esau, Jacobson then claims to promote peace. For example, he says Christianity’s war against Judaism proves that peace is possible, because Christianity was ‘tamed’. Translation: peace means the acknowledgement of Jewish supremacy.

Self-Serving Interpretations of Scripture

Based on a mix of sources, including the Zohar, Jacobson says ‘one regrets Hagar had Ishmael‘ (Ishmael was Abraham’s son through Hagar, Sarah’s handmaid). He points out that Ishmael was not circumcised until 13 years of age. As a result, God gave Ishmael’s posterity a portion for a period of time in Israel, and decreed that the children of Ishmael will rule the land for that time. But like their circumcision, which was not complete, it will be temporary. And it will be over a period of time when the land will be desolate. Then these people will prevent the children of Israel from returning to their place until the time has come to return the land to the Jewish people.

As a citation for this astonishing conclusion, Jacobson gives the page number: 32-A in the Zohar. I didn’t find his citations helpful, but I include them on the chance that someone else can use them. Then he continues: The children of Ishmael, the Arab nations and the Muslim nations, will cause great wars in the world, and the Children of Esau will gather against them. It’s a war between the West the the Muslim Arab world.

The Defeat of the Christian West

The war will go back and forth where the children of Esau, the Christians, and Romans and so on, will rule over the Ishmaelites. But the Children of Esau will not inhabit the land. The Holy Land will not be given over to them. At that time a nation from the ends of the earth will be aroused against evil Rome, and wage war against it for three months. Nations will gather there and Rome, referring to the Western World, will fall into their hands until all the children of Esau will gather against the nation, against that nation, from all the corners of the world. Then God will be roused against them. (And this is the meaning of the verse, for God is a sacrifice in Butra?). (That’s in Isaiah 3:46?) and afterwards it is written that it may take hold of the ends of the earth in (Job 38:31?) and he will defeat the descendants of Esau from the land and break all the powers of the nations, the nations’ guardian angels.

There will not remain any power of any people on earth except the power of Israel on earth (and this is the meaning God is your shade upon your right hand in the book of Psalms 12:15?), and then he concludes with verses talking about how ultimately we will come to the end of days, where on that day, God shall be one and his name one, and all the people of the nations of the world will recognize the name, and the truth of this one God each in their own way, (and that’s from the Book of Safia 3:9?) and then Blessed is God forever, amen and amen, and that’s how the Zohar ends.

False Humility

From here, he spends some time giving advice on humility and on how God wants harmony. But before peace can happen, there will be the period of these confrontations. What does that mean and translate in our lives he asks? That we all have within ourselves conflicts between our faith and the values that we believe in, and sometimes how do you implement that for example that has not compromised some of your ideals, due to so-called the realities on the ground. The challenge is how do you integrate the two.

Indeed!

Rothschild criticizes this belief system in more detail. For example, it is extremely disturbing that Chabad teaches similar divisions between peoples as the European far right. In this view, peoples of different nationalities belong to different species, with nothing in common. There is no universal man.

Modern Israel considers the West her enemy. And after squandering the West’s support, the Israeli’s believe that they will rule over the West with the approval of a Jewish God. Modern Israel is anti-West.

-

Irrationality as a Weapon Against the Enlightenment

I have previously criticized the Enlightenment, but now I think it may have been too easy to find fault. I was asking whether our present reality has benefitted from the Enlightenment’s promises. Now it’s time to compare Enlightenment thought to competing systems. In this article we will consider the Enlightenment from the point of view of the fascists. Probably the most disturbing revelation in Kevin Coogan’s book is the fact that fascists have purposely used irrationality as a weapon against the Enlightenment.

Since 1918, irrationality has been part of an assault on liberal notions of political discourse. This approach began as part of a Weimar intellectual current called the Conservative Revolution. 1 (Coogan p. 76). Today, we are seeing it at work in the United States. I believe this is the meaning of Kellyanne Conway’s ‘alternative facts’. It would also explain the behavior of Supreme Court justices who calmly demonstrate their disregard for legal argument and for the law itself. The fascist attack on the Enlightenment might help to clarify the Enlightenment’s importance to the West. If we want to avoid being overcome by this tactic, it’s necessary to recognize it for what it is.

Francis Parker Yockey’s Attack on American Rationalism

Among Francis Parker Yockey’s criticisms of Americanism was his claim that America’s Founding Fathers practiced a religion of Rationalism. He thought there were two key reasons that this ‘religion’ had been able to dominate America. The first reason was, America lacked tradition.

The second reason that rationality had been able to dominate America was that it had no originating ‘mother soil’ to provide Cultural impulses and Culture-forwarding phenomena. Rationalist religion came to America instead, through England. And it arrived in England by way of France (Coogan pp. 133-134).

Yockey argued that Europe had been able to resist Rationalism, thanks to tradition. Although he acknowledged that European tradition only lasted until the middle of the 19th century, he thought the European resistance had found support in Carlyle and Nietzsche. They proclaimed the coming of an anti-rationalist spirit in the 20th century.

Carl Schmitt

European Revolutionaries like Carl Schmitt shared Yockey’s belief that liberalism, democracy, individualism, and Enlightenment rationalism were the products of a superficial and materialistic capitalist society. The Revolutionaries yearned for the collapse of this order because its collapse would open the way for a new virile man of adventure. This man of adventure would be willing to risk all, due to an almost mystical belief in the state (Coogan p. 76).

In this Context, the Jewish Question is Never Far Away.

Yockey also argued that rationalist and materialist ideology made America vulnerable to domination by the Jewish ‘culture-distorter’. The Enlightenment was responsible, in his opinion, for opening up the West to Jewish influence. Jewish entry into Western public life would have been impossible if not for Western materialism, money-thinking, and liberalism–which he saw as Enlightenment concepts. These influences made America especially vulnerable to ‘Jewish capture’.

Feminism and the Irrational Right

Spengler called liberalism ‘the form of suicide adopted by our sick society‘; Yockey saw it as a sign of gender breakdown. According to Yockey, feminism was a means of feminizing man. In his opinion, man’s focus on his personal economics and relation to society made him a woman. The result in Yockey’s opinion was that American society is static and formal without the possibility of heroism and violence.

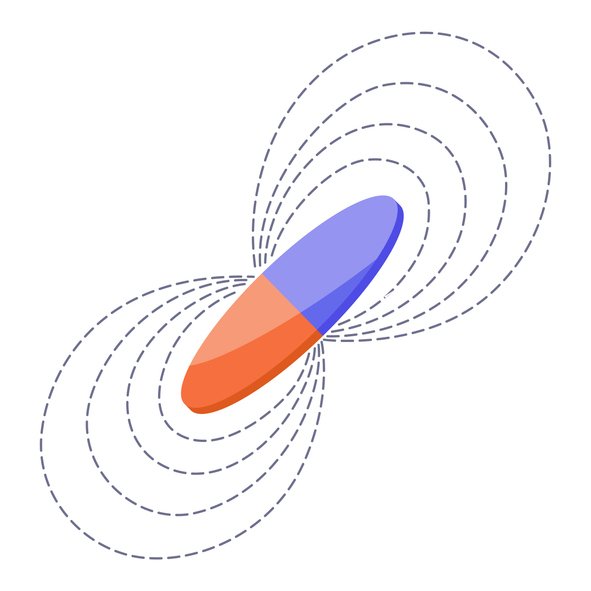

Polarity was a central concept for Yockey. Several of his polarities are listed on page 140 of Coogan’s book. He considered feminism and sexual polarity to be opposites. ‘Liberalistic tampering’ with sexual polarity would confuse and distort the souls of individuals.

Polarity, Credit: Designer_things The Right in general considered feminism to be against the natural order. However, the fascists’ definition of the natural order was different from that of the clerical and monarchist right. The old right still saw man as made in God’s image. By contrast, the Conservative Revolutionaries glorified the irrational, the wild, and the violent. At the same time, they were conflicted on this point.

They despised the Enlightenment argument that man was essentially a rational being who had been blinded by centuries of priestly superstition. But their confusion had to do with the irrational, wild and violent aspect of their belief system. They celebrated natural impulses, but the ‘natural’ pursuit of pleasure was in direct opposition to their idea of heroic life. They saw the pursuit of pleasure as weakness and degeneracy.

Rationalism or Polarity? Materialism or the Soul of Culture-Man?

In Imperium, Yockey wrote that the 20th century would bring about the end of Rationalism. Materialism would be no match against ‘the resurgence of the Soul of Culture-Man’. Unfortunately, the triumph of this new religiosity would not necessarily be a peace movement.

Conservative Revolutionary Ernst Jünger wrote in 1930 that modern war and technology were logical outgrowths of scientific progress. And war and technology had begun to undermine another Enlightenment idea–popular faith in reason. For Jünger, the real question was how to live in a new age of ‘myth and titanium‘ that was born in the trenches of Europe.

Jünger was one of the most decorated German soldiers in World War I. He believed that the sheer monumentalism of modern war had buried the idea of ‘individualism’ under a storm of steel. This marked the death of ‘the 19th century’s great popular church’, the cult of progress, individualism, and secular rationalism. In a world where a little man sitting far behind the front lines could push a button and annihilate the fiercest band of warriors, even battlefield heroics were meaningless.

Futurism built its mythology around speed, airplanes, and cars. Bolshevism gloried in an ecstatic vision of huge hydroelectric power plants stretching across the Urals. America saw the birth of the cult of Technocracy that viewed engineers as a new caste of high priests.

Coogan p. 141

In atheist Russia, even Stalin became a human god. Jünger wrote his essay The Worker to herald the coming of the new god-men of technology and total state organization in both the West and the Soviet Union.

Technocracy, Credit: kgtoh Time and Space

However, the far right’s thinking was already in flux before World War I. Coogan says there was a rebirth of mythological politics after the French Revolution (p. 141). This rebirth was brought on by the feeling that bourgeois constitutional democracy and civil society were obsolete. The rebirth of the mythic in the heart of the modern led the historian of religion, Mircea Eliade, to identify a nostalgia for the myth of eternal repetition. He thought he saw the abolition of time in the writings of T. S. Eliot and James Joyce. He called this ‘a revolt against historical time’.

In 1934, the Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse wrote an essay about the German new right. It was entitled The Struggle Against Liberalism in the Totalitarian View of the State. Like Eliade, Marcuse noted the right’s devaluation of time in favor of space, the elevation of the static over the dynamic…the rejection of all dialectic, in short, the deprivation of history (as cited by Coogan, pp. 141-142).

Pope Francis, on the other hand, Tells us that Time is Greater than Space

Progressives may not have understood Pope Francis when he told us that time is greater than space. That’s because he wasn’t necessarily talking to us. He was talking to the new right. Aleteia and other Catholic websites have explained it for those of us who didn’t get it the first time. Here I will try to explain the importance of this concept to the right.

Coogan explains the right’s thought process regarding time and space.

The turn to myth was intimately related in the quest for a new kind of post-Christian absolutism, since the new right rejected ‘God’. ‘Blood,’ not faith, was at war with reason, honor fought profit, ‘organic totality’ clashed with ‘individualistic dissolution’, Blutgemeinschaft [the community of blood] struggled against Geistgemeinschaft [the community of mind]. The Conservative Revolutionaries set as their task the creation of a new, virile warrior mythology. Right-wing Sorelians, they hoped that such a mythology would slow, if not reverse, Germany and Europe’s perceived decline.

Coogan p. 142

This phenomenon also called universal truth into question. One of its basic premises was that ‘Man’ did not exist. And if Man did not exist, neither did his universal rights. Only unique cultures existed–Germans, Frenchmen, Japanese, and Russians. What was ‘true’ was each cultures unique inner spiritual truth, and this could not be shared with other cultures. Nor was it subject to rational analysis.

The Left Resisted the Conservative Revolutionaries’ Glorification of Irrationalism

This glorification of irrationalism came under fierce assault from the left. But they had a unique understanding of its threat. The left identified Marxism as the logical heir of Enlightenment ideals. That said, we now know that Steven Pinker, who is not a Marxist, is also a defender of Enlightenment ideals.

Georg Lukács

Georg Lukács was a philosopher, literary critic and Stalinist. He argued that irrationalism begins at the same point of antinomy as dialectical thought. However, irrationalism deliberately ‘absolutizes the problem’. It calls into question the power of reason to ever know. In the absence of reason, faith and myth take center stage.

Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse stated the formulation of irrationalist theory: ‘Reality does not admit of knowledge, only of acknowledgment.’ In such an argument, ‘Life’ is the ‘primal given’. It is an existential or ontological state which the mind cannot penetrate. It follows that reason is actually hostile to life.

There are certain irrational givens (‘nature,’ ‘blood and soil,’ ‘folkhood,’ ‘existential facts,’ ‘totality,’ and so forth). These givens take precedence over reason. Reason is then causally, functionally, or organically dependent on those givens. Under such a paradigm, such existential facts became new absolutes. They are outside of time in the same way that myth is outside of time. Now antinomies are beyond the world of discourse and above historical mediation. In such a world, conflict between opposites could only be mediated by the stronger will. Will became to fascism what Reason was to the Enlightenment.

- Kevin Coogan, Dreamer of the Day: Francis Parker Yockey And the Postwar Fascist International, Autonomedia, Brooklyn, New York, 1999. ↩︎

-

Divisions in the Postwar Fascist International

Oswald Spengler was inside the Munich Beer Hall on November 8, 1923, when Hitler launched his putsch. Such encounters convinced him that the Nazis were the worst sort of proletarized street rabble. But although he cultivated an aura of political detachment, he was highly political. He wrote Prussianism and Socialism in 1919, in which he took part in the struggle against Russian-style Marxism, German social democracy, and Weimar liberalism. He once transferred funds from a right-wing German politician and former Krupp director named Alfred Hugenberg to one of the Bavarian paramilitary leagues known as the kampfbunde (Coogan pp. 58-59). This was the beginning of divisions in the postwar Fascist International.

The Right-wing versus the Nazis

Spengler was right-wing, but he was not a Nazi. As a political monarchist, he thought real government must be aristocratic, since every nation in history was led by an aristocratic minority. He voted for Hitler in the 1932 elections as part of a broad conservative bloc, but he believed that movements like Nazism were symptoms of Europe’s decline. Hitler’s populist rhetoric, as well as the Nazis’ hooliganism and pandering to the masses, reflected Germany’s problem rather than its solution.

In The Hour of Decision, Spengler attacked the political left for its noisy agitation as a foundation for individual power. But Ernst Roehm’s Stormtroopers were just as bad. Spengler also criticized Italian Fascism.

For Fascism is also a transition. It had its origin in the city mobs and began as a mass party with noise and disturbance and mass oratory; Labor-Socialist tendencies are not unknown to it. But so long as a dictatorship has ‘social service’ ambitions, asserts that it is there for the ‘worker’s’ sake, courts favor in the streets, and is ‘popular,’ so long it remains an interim form. The Caesarism of the future fights solely for power, for empire, and against every description of party (Coogan p. 59).1

Spengler Falls Out With the Nazis

The year Spengler’s book was published, 1933, was also the year the Nazis took power. The Nazis courted him at first, but when his book became an instant bestseller they tried to halt sales. They attacked Spengler’s ‘ice-cold contempt for the people,’ his worship of aristocratic and monarchist society, his pessimism, and his denial of race. (To be clear, Spengler, Francis Parker Yockey and others who argued against the racial basis for anti-Semitism, had no more love for the Jews than the Nazis did. They believed in Jew hatred, but in a more spiritual form.)

It didn’t take long for Hitler’s archivists to discover that Spengler’s great grandfather, Frederick Wilhelm Grantzow, was partly Jewish. In addition, Spengler was too close to Germany’s old ruling classes for comfort. His allies included wealthy business magnates and right-wing nobles like former German chancellor Franz von Papen. Last but not least, Spengler was not an anti-Semitic conspiracy theorist.

Educated Germany’s Contempt for Judaism, Islam and Christianity

Spengler shared the view of many educated Germans that Judaism was an exhausted belief system that had played out its historic vitality many centuries ago and only survived in Europe’s ghettos like a fossil preserved in amber. And these educated Germans were not any more friendly to Islam and Christianity. Spengler and his ilk even included the Nazi Volk in this group. He believed all of these belief systems were world-denying, escapist, and anti-historical. In his view, Western antipathy was not due to racism at all. It was cultural.

The Fascists Cherry-Pick Spengler’s Ideas

Francis Parker Yockey was completely on board with this view of race. However, unlike Spengler, he believed Hitler was ‘The Hero’, or the new Caesar, not because of but in spite of his ‘plebian racial musings’ (Coogan p 61).

Yockey Learns about Carl Schmitt at Georgetown

Carl Schmitt was Germany’s leading Catholic International and constitutional law theorist and an advisor to Franz von Papen during the Weimar period. He joined the NSDAP May 1933. Yockey became a devotee of Schmitt while studying at Georgetown University.

Yockey plagiarized Schmitt in Imperium. His defense of Machiavelli sounds eerily similar to that of Jacobin. Machiavelli’s book was defensive because Frenchmen, Germans, Spaniards, and Turks had invaded Italy during his century.

When the French Revolutionary Armies occupied Prussia, and coupled humanitarian sentiments of the rights of Man with brutality and large-scale looting, Hegel and Fichte restored Machiavelli once again to respect as a thinker. He represented a means of defense against a foe armed with a humanitarian ideology. Machiavelli showed the actual role played by verbal sentiments in politics (Yockey, as quoted by Coogan, pp. 74-75)

Carl Schmitt, the Conservative Revolution, the State of Exception, and the Messiah

Spengler inspired a Weimar intellectual current known as the Conservative Revolution. Novelist Ernst Junger and Martin Heidegger were part of it. They believed liberalism, democracy, individualism, and Enlightenment rationalism were part of a superficial and materialistic capitalist society. When the liberal order collapses, a new virile man of adventure will arise–a kind of Western ronin willing to risk all and with a mystical belief in the state.

Schmitt particularly despised Weimar parliamentary democracy. His theory for overcoming constitutional rule was the ‘state of exception, or ‘legal positivism’. This meant suspending the constitution during a crisis. He believed ending the constitutional order opened a path for a new heroic ‘politics of authenticity’.

Like Spengler, Schmitt saw the state as supreme. He believed government proceeded in three dialectic states: from the absolute state of the 17th and 18th centuries; through the neutral state of the liberal 19th century; to the totalitarian state in which state and society are identical.

Father Walsh observed that the final stage of Schmitt’s idea ‘was the monopoly of all power, all authority, all will in the Führer, conceived and accepted as Messiah endowed with unlimited legal prerogatives in a state under perpetual martial law.’

Schmitt Endorsed Hitler’s Night of the Long Knives

Schmitt endorsed Hitler’s bloodletting on The Night of the Long Knives, but the killing cut both ways. Hitler also used the purge to intimidate his potential rivals in the old military and political establishment who had given him political respectability. He even murdered one of Franz von Papen’s closest aides. The following quote is the Nazi challenge to the old guard.

“If we had relied upon those suave cavaliers (the reactionaries), Germany would have been lost. These circles sitting in armchairs in their exclusive clubs, smoking big cigars and discussing how to solve unemployment, are laughable dwarfs, always talking and never acting. If we stamp our feet, they will scurry to their holes like mice. We have the power and we will keep it” (Joseph Goebbels, June 1934, as quoted by Coogan, p. 77).

The Nazi’s Turn Against Schmitt

In 1936, the Nazis turned on Schmitt and began investigating his ‘non-Aryan’ wife. The SS organ Das Schwarze Korps regularly threatened him. According to Coogan, this was simply a power-play by Himmler to seize total police and judicial power.

Schmitt Retreats to Geopolitics with His Grossraum Theory

In response, Schmitt turned to international law. In 1939, he gave a speech to the Institute of Politics and International Law at the University of Kiel about the legitimacy of an extraterritorial order, a ‘great space order.’ His rationale: the nation-state system had broken down. Now the world had the British, Soviet and American empires, as well as Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere. These dwarfed older concepts of ‘nation.’ Enormous shifts in state power demanded corresponding shifts in international law. Grossraum was the proper way forward. Grossraum referred to an area dominated by a power. This would not be the result of organic geopolitical expansion but of a ‘political idea’. Schmitt had in mind a German-dominated Central Europe. This was a political idea distinct from its two universalist opponents–the laissez-faire ideology of Anglo-Saxon capital and the equally universalist Communist ideology. It was a German version of the American Monroe Doctrine.

This impressed Hitler. It also influenced Chamberlain’s agreement with Hitler over Eastern Europe’s 1939 Munich Agreement.

Yockey Objects to Schmitt’s Materialism; Haushofer Praises Schmitt; the Nazis Defend the Third Reich’s Racial Justification

Yockey’s criticism of Schmitt focused on Schmitt’s materialism. He said the traditional geopolitics of Schmitt was based on physical facts or geography. Instead, the soul is primary. But at the same time, he believed Schmitt’s researches had permanent value and that large-space thinking was essential.

Yockey praised Haushofer; Haushofer supported Schmitt; and the Nazis disagreed with Haushoffer and Schmitt. Haushofer thought Europe needed a concept like pan-Slavism or pan-Asianism–ideas seeking to manifest themselves in space. Nazi racialists argued that pan-Slavism or pan-Asianism would remove the racist justification from the concept of the German Reich.

Yockey and Newton Jenkins

While Yockey was attending Northwestern’s law school in Chicago, he served as a ‘kind of aide-de-camp’ to a lawyer and important right-wing activist named Newton Jenkins. Jenkins had found his way to fascism from the progressive movement.

Jenkins went to school at Ohio State and Columbia University’s Law School. After serving in World War I, he returned to the Midwest and became legal counsel for many farm groups and agricultural cooperatives. He also began working closely with the Progressive Party and used his radio program to support FDR for President. However, in 1932 he ran for senate in the Republican Party’s primary and was able to win 400,000 votes.

The Yockey-Jenkins connection came to the FBI’s attention through an informant. This informant had seen a March 31,1954 column by Drew Pearson, which attacked Soviet ties to the far right. In his column, Pearson revealed that the FBI was interested in Varange (Yockey’s pen name in Imperium), and he identified Varange as Francis Parker Yockey. As a result, a former acquaintance of Yockey’s from the late 1930s contacted the FBI. According to FBI files, this informant met Yockey in 1938 at the Chicago office of Newton Jenkins. An excerpt from the report follows.

_______recalls that Yockey was an intense, secretive, bitter individual who did not tolerate anyone who would not wholeheartedly agree with his solution to world problems…_______stated that…Yockey was ‘power hungry’ and gave the impression that he would not stop until he became the most powerful individual in the world. _______believes that Yockey will not succeed in this because he creates too may enemies. ________feels that Yockey will go along with any program whether it stemmed from Moscow, Buenos Aires, Yorkville, Tokyo or Washington, D.C., as long as he can be the leader. ________stated that Yockey believed that the world capitalist structure was about to crumble and that fascism was the only solution, but he insisted that it be the Yockey form of fascism and none other…

Coogan pp. 85-86

Jenkins Progressivism

Jenkins was active in promoting the America First Committee the Keep America Out of War Committee, and similar organizations working for the defeat of Russia and Communism. He also maintained ties to the German American Bund. According to George Britt’s 1940 book, The Fifth Column is Here, Jenkins has an extensive record of pro-Hitler comments. Also, Jenkins attempted to unite fascist and Nazi groups into a third political party. This led the Bund to christen him The Leader of the Third Party (cited by Coogan).

Jenkins Makes a Right Turn

Jenkins began his right turn in 1934 when he formed The Third Party under the slogan ‘U.S. Unite?’ Party headquarters was 39 South La Salle Street, the same office where the FBI informant had met Yockey. In his pamphlet, The Third Party, Jenkins portrayed himself as a progressive opposed to big business. He explained that he was founding his new organization because Franklin Roosevelt had backed down on implementing the more radical aspects of the New Deal. He also warned that the British Empire had too much influence over American foreign policy.

Jenkins favored active government intervention in the economy and thought Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany were models for America. To support his efforts, Jenkins began contacting Hitler’s supporters in the ‘Friends of the New Germany‘, which soon became the German-American Bund.

The German-American Bund, the Union Party, and Jenkins’s Ambition to Unite 125 Rightist Groups

In 1936, Jenkins became campaign manager for the Union Party, which turned out to be the most significant third-party challenge to FDR. After the Party’s defeat, Jenkins maintained relations with the Bund. He spoke at the Bund’s 1937 National Convention at Camp Siegrried in New York. He then launched his own paper, American Nationalism, which served as the propaganda arm of yet another Jenkins organization, the American Nationalist Political Action Clubs (ANPAC). This organization aimed to unite over 125 rightist groups into a coordinated movement (Coogan, pp. 87-88).

Yockey Was a Weimar ‘New Right’ Anti-American

Yockey’s attraction to both Spengler and Conservative Revolution theorists like Carl Schmitt made him virtually unique in the American far right. American supporters of Nazi Germany were usually German Americans, crude anti-Semitic nativists, or staunch conservatives who viewed Hitler as a heaven-sent bulwark against Bolshevism. By contrast, Yockey represented a Nazified version of the Weimar “New right” Conservative Revolutionary current.

Yockey devoted over a hundred pages of Imperium to describing an America incapable of ‘destiny thinking’. In this he was heavily dependent on Oswald Spengler, who had the following to say about ‘hundred percent Americanism‘:

A mass existence standardized to a low average level, a primitive pose, or a promise for the future?…America with its ‘intellectually primitive upper class, obsessed as it is by the thought of money, lacked that element of historic tragedy, of great destiny, that has widened and chastened the soul of Western peoples through the centuries. America was little more than a boundless field and a population of trappers, drifting from town to town in the dollar-hunt, unscrupulous and dissolute, for the law is only for those who are not cunning or powerful enough to ignore it (Spengler paraphrased by Coogan p. 132).

Spengler goes on to liken the United States to the Russian form of State socialism or State capitalism. It doesn’t grow organically. It grows through soulless mechanization. (You will recall that the idea of an ‘organic’ state was the first heresy of German geopolitics according to Father Walsh. Here Spengler faults the United States for growing mechanically, rather than organically.)

Yockey was every bit as insulting as Spengler. Coogan sums Yockey’s arguments up this way: ‘A Nation, in short, is a people containing a Cultural Idea. Because America lacks a Cultural Idea, America, by definition, is not a nation.’

Yockey also faults what he called the ‘Rationalist Religion’ of America’s Founding Fathers. He argued that this ‘Religion’ came from England through France. But rationalism did not dominate Europe until the 19th century, thanks to Europe’s tradition. America never had this tradition. Furthermore, America’s rationalist and materialist ideology made her vulnerable to domination by the Jewish ‘culture-distorter’.

Yockey’s racism was intense and visceral (Coogans words). It also had ideological roots. Coogan supports this argument with quotes from Hegel’s The Philosophy of History. Yockey was dealing with his own racism, Hegel’s influence, and Spengler’s description of great cultures (Coogan p. 135). For more of Yockey’s criticism of America see Coogan’s Chapter 14, Empire of the Senseless.

Imperium: a New Kind of Fascism

Coogan says the enthusiasm of rightist leaders for Yockey’s book, Imperium, reflected a need for a new kind of fascism. He cites the call for a united Europe by Sir Oswald Mosley. Mosley envisioned ‘a great unity imbued with a sense of high mission, not a market state of jealous battling interests.’

The Right’s Doubts About Yockey

But Mosley turned against Yockey. Mosley not only declined to publish Imperium, he blocked a promised review in the Union Movement paper. This brought much criticism from prominent members of Mosley’s group who wanted more dynamic leadership. Mosley’s biographer Robert Skidelsky explained Mosley’s rationale.

It was part of a process of Mosley’s extrication from the dead hand of pre-war fascism and a rededication to a new, and more moderate crusade. This meant coming to terms with American hegemony over Western Europe. It was this approach that Yockey opposed.

While still in Mosley’s group, Yockey had had discussions about the American question with A. Raven Thomson, one of Mosley’s closest aides. Thomson later wrote in a letter to H. Keith Thompson that Mosley had refused to finance Yockey’s book because it was full of Spenglerian pessimism and unnecessarily offensive to America. After Yockey broke with Mosley’s group, they found him to be ‘so conceited and unstable in personal relations that it is almost impossible to work with him‘ (Coogan, p. 171).

Coogan adds a historical explanation for the break: The political climate in Europe in 1948 had become dangerous, with the Berlin Crisis raising the possibility of war. Suddenly the fascist ‘third way’ was called into question.

Yockey Turns to the East

Eventually, Yockey’s book was financed by Baroness Alice von Pilugl. It was during his association with Pilugl that Yockey began advocating far-right cooperation with the Russian conquest of Europe (Coogan p. 172). And this was not the only attempt to ally the radical right with the USSR.

An anti-Yockey British-German group called NATINFORM (the Nationalist Information Bureau) observed Yockey’s meetings. By 1950, it was clear that Yockey et al were promoting a definite line of policy and seeking collaborators. The main trend of this policy was based on Imperium and Yockey’s concepts. In July of 1950, Guy Chesham, who was acting as a representative of Yockey, outlined a policy of infiltrating into all Nationalist groups with a view to seizing control from within or organizing sabotage.

The political direction of this activity was to be violently anti-American, avoiding all anti-Bolshevist conceptions. No anti-Jewish propaganda was to be permitted [at] first (Coogan pp. 173-174).

Yockey Has Company

Yockey was not acting alone in this effort. The right-radical Socialist Reich Party (SRP) was founded in Germany aroung the time of Imperium’s publication. It called for a pro-Eastern neutralist Germany, which was almost identical to Yockey’s position. Yockey’s organization, The European Liberation Front (ELF) was in some respect the SRP’s British cousin.

Two Russias

In the Russia chapter of Imperium, Yockey argues there are really two Russias: The first Russia, symbolized by Peter the Great, wanted to imitate the high culture of the West. But neither Peter nor his successors could implant ‘Western ideas below the surface of the Russian soul’.

…the true spiritual Russia is primitive and religious. It detests Western Culture, Civilization, nations, arts, State-forms, Ideas, religions, cities, technology. This hatred is natural and organic, for this population lies outside the Western organism, and everything Western is therefore hostile and deadly to the Russian soul.

According to Yockey, the Russian Revolution was a revolt of both Russias, the Marxist Western-oriented intelligentsia, and the anti-Western underclass.

The European Liberation Front and Strasserism

Some denounced Yockey and his European Liberation Front (ELF) for being Strasserists. Arnold Leese of the British far right denounced them in the early 1950s. The American Nazi leader George Lincoln Rockwell would label ‘Yockeyism’ a Strasserist perversion of true National Socialism.

Coogan defines Strasserism historically as the anti-big business northern wing of the Nazi Party. It was led in the mid-1920s by the brothers Gregor an Otto Strasser. They mainly recruited factory workers in the industrial north. The Strassers insisted that the Nazis were socialists who would break up the domination of big capital and the vast landed estates and called for an alliance with Russia and the ‘East’ against England and France. (England and France represented the hated enforcers of the Versailles Treaty.) Hitler was angry about their propaganda and their independent power base. He drew his strength from the more conservative Bavaria.

Otto Strasser created the Black Front after he quit the NSDAP to protest Hitler’s alliance with big business and aristocratic elites like the Krupps and the Papens. The Black Front was ‘Strasserist’. Hitler murdered Gregor in 1934 during the Night of the Long Knives.

Historically Yockey was not a Strasserist, but he was a small-s-strasserist in some ways. He had a national Bolshevist foreign policy, rejected biological determinism and hated capitalism. He also maintained ties with Alfred Franke-Gricksch, a key leader of the postwar German far right and a former member of Otto Strasser’s Black Front.

Yockey, Franke-Gricksch, and the Bruderschaft

Both Yockey and Alfred Franke-Gricksch advocated close cooperation between the far right and the East Bloc. The ELF, was also linked to Franke-Gricksch, who was the leading German advisor to the Union Movement at that time. Through Franke-Gricksch, Yockey established relations with an organization referred to as the Bruderschaft (Brotherhood) in Germany.

The Brotherhood was one of the most important groups in Germany’s postwar fascist elite. They used intelligence and organizational contacts with fascist movements around the world to play a role in the Nazi underground railroad that smuggled war criminals to South America and the Middle East. Franke-Gricksch had joined Major Helmut Beck-Broichsitter soon after he founded the Bruderschaft in a British POW camp in 1945-46. In addition, Franke-Gricksch brought with him a plan to recapture power by slow methodical insinuation into government and party positions.

Franke-Gricksch joined the Strassers’ northern wing of the NSDAP. He also became a founding member of the Black Front. Franke-Gricksch went into exile with Otto Strasser after Hitler took power, but later he deserted the Strassers. He may have been responsible for the destruction of the Black Front after his defection. Shortly after he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the SS, the Gestapo was able to penetrate and liquidate the underground apparatus of the Black Front.

Franke-Gricksch’s son, Ekkehard, explained his father’s pre-war activity in a letter to Willis Carto’s Institute for Historical Review. He said that Hitler had distanced himself from his original National Socialist goals. After Alfred Franke-Gricksch fled the country, he returned and came to an agreement on this point with Himmler. He secretly joined the Waffen SS under the name Alfred Franke.

Alfred Franke-Gricksch’s and the German Freedom Movement

According to Coogan, Franke-Gricksch’s activity at the end of the war is more of a concern than his activities during the war. In April 1945, Franke-Gricksch was the head of the Personnel Section of Himmler’s RSHA (the Reich Security Main Office). This was Nazi Germany’s CIA. He spent the last days of the war preparing a blueprint for a postwar fascist Europe. This was The German Freedom Movement (Popular Movement). Among other demands…

it demanded a Nazi Party purge to free it ‘from a degenerate party bureaucracy and the…party bosses, from a ruling caste in State, Party, and Party organizations, which has deceived itself and others for years’ (p. 194).

The German Freedom Movement outlined a new pan-European foreign policy program. It included a 12-point ‘European peace settlement’ and a new ‘Sworn European Community’ of peoples. A ‘European arbitration system’ would secure some form of voluntary allegiance to a ‘Germanic Reich.’

One scholar described Franke-Gricksch’s plan as being based on the ‘call of the blood’ but tempered ‘by the introduction of a federal system and excluding any claim to sole leadership by Germany.’

This movement envisioned a post-Hitler Europe freed from the biological exaltation of the German race. SS technocrats had developed a similar concept. Their ranks included SS Brigadier General Franz Alfred Six.

Pan-European Fascism and the Rehabilitation of Carl Schmitt

SS Lieutenant General Werner Best was another advocate of pan-European fascism. He was a former Conservative Revolutionary, a fan of Ernst Jünger, and a counter-intelligence expert with a doctorate in law. He later became a director of Amt II, which supervised administrative, economic, and judicial matters for the RSHA. Franz Alfred Six was his first AMT II assistant.

From 1940 to 1942, Best was in charge of civil administration for all of occupied France. Then, in December 1942, he became Reich Plenipotentiary to Denmark. He used his power to rehabilitate Carl Schmitt inside the SS because he saw that Schmitt’s Grossraumordnung theory could be useful in the legal reconstruction of Europe. This allowed Schmitt to lecture to elite audiences throughout occupied Europe and Spain.

In Schmitt’s testimony at Nuremberg, he explained that Best’s circle wanted to become an intellectual elite and form a kind of German ‘brain trust’. But since a brain trust was a contradiction in Hitlerism, the concept of Grossraum became their touchstone.

The Reinvention of Fascism and Coogan’s Suspicions About Yockey

After Hitler’s suicide, technocrats like Best, Six, and Franke-Gricksch were free to reinvent fascism. This plan went forward in spite of the fact that until the autumn of 1948, Franke-Gricksch was in a POW camp in Colchester, England. He maintained his leadership position inside the Bruderschaft while in prison. After his return to Germany, he became the group’s ideological leader. Franke-Gricksch preached that the mission for the Bruderschaft was to midwife the creation of a new kind of elite rule now that ‘the era of the masses has passed.’

Coogan suspects that Yockey was acting in concert with the Bruderschaft while he was in Wiesbaden. Sometime in 1948, Yockey began publicly arguing in London that Russia was the lesser of two evils. Then, in 1949, after Franke-Gricksch had returned to Germany, Yockey, Guy Chesham, and John Gannon founded the ELF.

Divisions in Italian Fascism

There were also postwar divisions in Italian fascism. The divisions inside the MSI dated back to 1943, when the Fascist Grand Council deposed Mussolini. Italy’s Movimento Sociale Italiano (or MSI) was the largest and best-organized fascist movement in postwar Europe. After the Nazis freed Mussolini from an Italian jail, he established a new government known as the Salò Republic in the Nazi-held north of Italy. Subsequently, former fascist leaders and veterans of Salò’s National Republican Army founded MSI.

Because Mussolini believed his downfall was the fault of the old Italian elites, he returned to fascism’s radical roots and demanded the nationalization of Italian industry. After the war his Salò Republic supporters continued to represent a kind of northern Strasserist tendency inside Italian fascism. However, a more moderate wing of the party defeated the Salò radicals at the June 1950 convention. By the fall of 1951, the MSI had reversed its earlier opposition to Italian participation in NATO.

The Radical Wing of the MSI Accepts Yockey’s Imperium

Yockey’s Imperium especially appealed to the most radical wing of Italy’s MSI. MSI’s founder Giorgio Almirante praised Imperium after its publication. Almirante spoke for MSI hardliners opposed to turning the group into a purely parliamentary organization. Yockey was a member of this anti-MSI hard right.

Julius Evola

The journal, Imperium, published Evola’s first postwar political statement in 1950, in which Evola argued against all forms of ‘national fascism’ (including the Salò Republic). He demanded instead a new ‘Gemeinscaft Europas’ best symbolized by the Waffen SS. The arrest of Evola in June of 1951 was one example of the complex political situation in Italy in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Political Pragmatism and NATO in Italy

Italy’s Christian Democrat-led government, and its supporters inside both the Vatican and the CIA, needed the far right to help them oppose the Communists. Many MSI members, however, objected to any cooperation with the state. The MSI had only two options: It could continue to maintain a revolutionary ‘anti-bourgeois’ stand while having some parliamentary presence, or it could accept the status quo and become a full parliamentary organization. A second great choice involved foreign policy. Which superpower was Italy’s main enemy–Russia or America?

Advocates of the parliamentary road generally accepted the postwar order, which included Italian support for NATO. Rejectionists insisted on anti-American neutrality, with some even open to a tactical tilt East. The MSI’s founders, supporters of the Salò Republic, held radically anti-bourgeois ‘left’ corporatist fascist views. Almirante, for example, had earlier helped create the Fasci di Azione Rivoluzionaria (FAR) in 1946.

FAR member Mario Tedeschi said that real fascism had been subverted by conservative forces during the ventennio [twenty years] of power. He accused the monarchy and the plutocratic bourgeoisie of conspiring to bring down Mussolini in 1943. FAR violently opposed the Italian Communists, while at the same time hurling bombs at the U.S. embassy in Rome. FAR members claimed they were remaining true to the radical ideals of Salò.

Italy’s Communist Party (the PCI)

However, MSI’s fear of Italy’s Communist Party (the PCI) caused it to form anti-PCI electoral blocs with the Christian Democrats in Rome and other cities. MSI’s biggest electoral base was also in the conservative south, where a more pragmatic and traditional ‘southerner’ Augusto De Marsanich defeated Almirante in January 1950 for the position of MSI general secretary.

One key to Almirante’s downfall was that he had opposed NATO. In the spring of 1949, the MSI had voted against any Italian role in NATO. But after a bitter debate at the party’s congress in June, the group reversed itself and accepted NATO membership. Not long after that, De Marsanich took power. At this point, the Italian Communist Party began to court the MSI’s anti-NATO wing.

Young Radicals Try to Escape the Embrace of the Christian Democrats and the Communists

In the war between the ‘left’ and ‘right’ wings of Italian fascism, many young radicals tried to escape the embrace of either the Christian Democrats or the Communists. They considered these parties surrogates for the Americans or the Russians. In the early 1950s, veroniani like Pino Rauti, Clemente Graziani, and mario Gionfrida organized gang-like paramilitary groupings. Believing that democracy was a ‘disease of the soul’, they turned to Baron Evola for inspiration.

Evola Criticises Yockey and Fascist Youth

Evola and Yockey had much in common. They were both admirers of Spengler and held similar views on the question of race. And Evola thought Yockey’s book was important. However, he posed questions for Yockey and a whole generation of fascist youth.

Evola thought Varange (Yockey’s pen name in Imperium) had fundamentally misread Spengler by not taking seriously enough his emphasis on the difference between Kultur and Zivilization. Civilization could only be a time of decline. Yockey insisted on building the Imperium even though the formation of a super-rational and organic united Europe was inconceivable. Furthermore, Yockey had confused the age of Caesarism with the coming of Imperium. His belief that the breakup of the Third Reich made way for the emergence of a pan-European new fascist movement was romantic nonsense in Evola’s view. The NSDAP was a problematic formation in the first place and its breakup could not be transformed into a harbinger of a coming victory.

Dada: Evola’s Long Assault on the Bourgeois Order

Evola first began his assault on the bourgeois order as Italy’s leading exponent of Dada. He collaborated on the Dada journal Revue Blue, and often read his avant-garde poetry in the Cabaret Grotte Dell’Augusteo. He exhibited his Dada paintings in Rome, Milan, Lausanne, and Berlin. Inner Landscape 10:30 A.M. is still displayed at Rome’s Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna.

Evola discovered Dada in high occultism. There, he learned that it was a dissolution of outdated art forms. In the mid-1920s, he studied magic, alchemy, and Eastern religion as part of Arturo Reghini’s Gruppo di Ur. Reghini claimed to be a representative of the Scuola Italica, a secret order that had supposedly survived the downfall of the Roman Empire. He was a major figure in many Italian theosophical and anthroposophical sects and became a leader of the Italian Rite in Freemasonry. The Italian Rite, created in 1909, was allied with the anti-clerical Plazza del Gesu branch of Masons.

In 1927 Evola published Imperialism pagano, which denounced Catholicism’s influence on Italian culture starting with the alliance between the Church and State begun by the Roman Emperor Constantine. Evola’s denunciation led Father Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, to attack Imperialism pagano. In the Catholic magazine Studium, Montini used Evola’s writings to show what could happen to those who become too obsessed with a ‘metaphysics of obscurity, of cryptology of expression, of pseudo-mystical preciosity, of cabalistic fascinations magically evaporated by the refined drugs of Oriental erudition.’

Evola and René Guénon

Through Reghini, Evola learned of a French Orientalist named René Guénon. Guénon was an important figure in the European occult underground. Evola completely embraced Guénon’s argument that the modern age’s interest in democracy, mass culture, and materialism are all manifestations of the Kali-Yuga. Guénon taught that the Kali-Yuga had infected thinking to the point where Western philosophy has become ‘purely human in character and therefore pertaining merely to the rational order. This rational order replaced the genuine supra-rational and non-human traditional wisdom (Coogan p. 294).

Evola considered fascism another expression of the Kali-Yuga. In this way, he shared Spengler’s objections to Mussolini and Hitler’s pandering to the masses. However, Evola thought the dissolution that came with fascism would clear the way for a new Golden Age.

Even though Evola borrowed Guénon’s ideas, the two men became rivals in a way. Guénon eventually rejected contemporary spiritualistic and theosophic fads in favor of ancient spiritual traditions (Traditions). Evola, on the other hand, refused to separate man from the Gods.

- Kevin Coogan, Dreamer of the Day: Francis Parker Yockey and the Postwar Fascist International, Autonomedia, Brooklyn, New York, 1999. ↩︎

-

Realists and the Radical Right

In a previous article I wrote about Professor Wen Yang’s YouTube video in which he argued that the Anglo-Saxons are the worst people ever. He said this was the result of the Anglo-Saxons having missed the Axial Age. Interspersed with Yang’s portion of the video was a speech by Jeffrey Sachs. Both men use similar criteria to condemn the United States. Sachs blamed what he believes is a breakdown in Anglo-Saxon culture on the degeneration of Western Philosophy. I have argued that both arguments are flawed, and I refuted their claims in two articles. Sach’s focus on the influence of Niccolò Machiavelli in Western politics was the subject of one article. The other article was about Professor Yang’s claim that the Anglo-Saxons missed the Axial Age. This study led me to ask why they would make such false claims. I have concluded that the criticism of Anglo-Saxon countries is motivated by ideology. This article and subsequent articles will expand on this idea. This article will cover Realists and the Radical Right.

The Radical Right During and After World War II

Misrepresentation may not have been conscious on the part of Yang and Sachs. Currently, the rise of the radical Right is one of the most important challenges faced by the US government, but it is not mentioned in the field of International Relations. The ideologies of the radical Right have been forced underground since World War II, and sometimes its ideology creeps in unrecognized. Realists have tried to guide the conversation away from it, hoping it will go away. As a result, we are all shocked to discover that the radical Right has made a ‘comeback’.

A paper published in 2021 in Review of International Studies (RIS) 1 provides an explanation for this omission. Authors, Jean-François Drolet and Michael C. Williams, explain how and why the discipline of International Relations (IR) eliminated the radical right’s point of view.

This is not a condemnation of realists. It’s hard to argue with the rationale of those who carried out this plan. Social scientists feared the radical Right’s negative influence on the civil rights movement and other campaigns. And they saw anti-liberal ideas as a threat to peace and democracy. This is the context in which International Relations developed.

Today, radical Right ideas have burst into the open, and the realists’ fears have proven to be correct. At this time, it’s important to confront the fact that IR’s origins were framed as a battle between liberalism and realism. The Mearsheimer/Pinker debate, in which Steven Pinker defended liberalism and John Mearsheimer defended realism, is a good example.

The organization of this material

Drolet’s and Williams’ paper is a comprehensive treatment of this problem. It lays out a key part of the history of right-wing ideologies in the United States. It also discusses the people and organizations that fought them. I plan to divide this paper into sections and cover each one in its own article. This article will focus on the men and ideologies of the radical Right, as well as their influence in the United States.

The Failure of International Relations Credit: imaginima The Failure of International Relations

In the past decade, transnational networks of the radical Right have made gains in Europe, North America and beyond. Governments and political parties with conservative foreign policies have increased as a result. These networks and parties routinely use the ideology of the radical Right to contest prevailing visions of the global order. Their aim is to weaken established forms of international governance.

Drolet and Williams argue in their paper that understanding the intellectual history of the discipline of IR will increase our understanding of right-wing thought, as well as the realist tradition. Their account should also help progressives develop a coherent identity and strategy.

Militant Conservative Ideas in Global Postwar Politics

Right-wing influencers were present in the West both during and after World War II. Much of the literature about these individuals focuses on European thinkers after 1948. Americans remain unaware that a similar influence was present in the United States during the same period. Right-wing ideologues were engaged with international security, geopolitics and Cold War strategy. Their ideology tended to be skeptical or hostile to liberal modernity. They insisted on racial hierarchies, cultural foundations, tradition and myth, as the basis of society.

Drolet and Williams focus on four influential conservative voices in American foreign policy and international affairs. They include Robert Strausz-Hupé; James Burnham; Stefan Possony; and Gerhart Niemeyer. These men were not unified theoretically. However, they were aware of each other’s work and knew each other personally. In addition, they often collaborated with each other and supported the same political causes.

All four men were backed by philanthropic foundations and engaged in Journalism and public debate. They wrote bestselling books and influential columns and lectured at US military and training colleges, and set up training programs based on their ideas. In addition to advising political leaders and candidates, they held government positions or consultancies. Surprisingly, they were also involved in the theory of International Relations. All of this activity took place while they held influential academic positions in leading American universities.

Robert Strausz-Hupé

Robert Strausz-Hupé immigrated to the United States from Austria in 1923. Initially, he worked on Wall Street and as editor of Current History Magazine. He joined the University of Pennsylvania’s political science department in 1940. Strausz-Hupé wrote more than a dozen books, including a book on international politics which he co-authored with Stefan Possony. In addition, both Strausz-Hupé and Gerhart Niemeyer were part of a Council on Foreign Relations study group in 1953 on the foundations of IR theory. In 1955, Strausz-Hupé established the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI) at the University of Pennsylvania, with the backing of the conservative Richardson Foundation. He also founded its journal, Orbis. The FPRI quickly established ties to the military, causing Senator Fulbright to denounce them as reactionary threats to American Democracy.

Strausz-Hupé was a foreign policy advisor to Barry Goldwater in his 1964 presidential campaign. He also advised Richard Nixon in 1968, and served as US ambassador to NATO, Sri Lanka, Belgium, Sweden and Turkey.

The Influence of German Geopolitik

Strausz-Hupé’ is remembered today, for his geopolitics. His connections to the radical right come to light in this context. Geopolitical ideas and reactionary politics go together, according to Drolet and Williams.

Geopolitics became linked to organic state theories and global social Darwinism through nineteenth century theorists like Friedrich Ratzel or Rudolph Kjellen. Kjellen, a Swedish political scientist, geographer and politician was influenced by Ratzel, a German geographer. Ratzel and Kjellen, along with Alexander von Humboldt and Carl Ritter, laid the foundations for the German Geopolitik. Later their Geopolitik would be espoused by General Karl Haushofer. Haushofer influenced the ideological development of Adolf Hitler.

Haushofer visited Landsberg Prison during the incarceration of Hitler and Rudolf Hess by the Weimar Republic. He was a teacher and mentor to both men. Haushofer coined the political use of the term Lebensraum, which Hitler used to justify crimes against peace and genocide.2

German Geopolitik’s Political and Cultural Turn

German Geopolitik was inseparable from expansionism, racial or societal international hierarchy, and inevitable conflict. It became more political and cultural through radical conservative thinkers like Oswald Spengler, Moeller van den Bruch, and Carl Schmitt. Culture, race and myth developed as its core, and its urgent focus became the fate of the West.

Spengler insisted Western Civilization was in terminal decline, but Moeller was not so pessimistic. Moeller argued that Germany and Russia were young and vibrant cultures that could escape the decadent Anglo-American Civilizations and flourish in a continental partnership that would dominate the future. Similarily, Haushofer held that Eurasian land power was the geographic pivot of history, and viewed the ‘telluric’ Eurasian land powers as inescapably at odds with the ‘thalassocratic’ Anglo-American sea powers.

Geopolitics in a European and German setting was profoundly conservative and often reactionary. Many of its proponents rejected liberal visions of politics and were especially hostile towards the United States and Britain. German Geopolitik advocated a political geographic determinism opposed to the idea of a Euro-Atlantic partnership. They claimed Europe was the true West. Europe was not part of the Atlantic world, but an alternative to it.

Making America Geopolitical

Strausz-Hupé and other European émigrés taught geopolitics in America. Edmund Walsh, founder of Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, joined them in this task. These men taught a version of the Cold War that was a geopolitical critique of liberal modernity. They argued that the Cold War was evidence of a deeper civilizational and metaphysical crisis. These statements had the appearance of analytic objectivity, but the appearance was used to justify a blunt form of power politics.

These men purportedly avoided the German formulation of geopolitics. Unfortunately, Strausz-Hupé’s description of German geopolitik was based on his racial categories and assumptions about European colonialism. He argued that there were two distinct versions of geopolitics. In his version, statesmen used geopolitics to achieve a balance of power. In the Nazi version, geopolitik was used to destroy the balance of power and wipe out all commitments to the shared Christian heritage of Western civilization. German geopolitik had been turned into the doctrine of nihilism and the antithesis of the principles of proper order because it had given up the trappings of Western Civilization.

Strausz-Hupé Borrows Key Concepts from German Geopolitik

Strausz-Hupé himself doomed this right-wing attempt to distinguish between German geopolitik and American geopolitics. First, he endorsed the German neo-Darwinian vision of international relations as an everlasting struggle for world domination. He proposed that regional systems must be established, each one clustered around a hegemonic great power. Finally, geography and technical mastery designated America as the new epicenter of the West. All the races of Europe would use America’s military capabilities to create a stable world order out of the defeat of the Axis Powers. But there was one condition.

Everything depended on the US leading the fight against Communism and creating an order under which a federated Europe could be subordinated within NATO. Anything short of this, including benign interpretations of the USSR’s motives would be disastrous.

In Strausz-Hupé’s view, liberals failed to recognize that periods of peaceful, competitive coexistence were as much a part of the communist war plan against the Free World as periods of aggressive expansion. Liberalism and containment-focused realists were not capable of sharing Strausz-Hupé’s global vision. Instead, Strausz-Hupé suggested abandoning containment and using superior military power to ‘rollback’ and ultimately destroy communism. The United States must develop a military posture and strategic doctrine that maintained nuclear deterrence, but allowed America to fight limited wars and prepare for the possibility of a total nuclear war.

James Burnham

James Burnham agreed with Strausz-Hupé’s anti-Communism, power politics and attacks on liberal decadence. Burnham was a philosophy professor at New York University from 1929 to 1953. He lectured frequently at the Naval War College, the National War College, and the John Hopkins School for Advanced International Studies, and was a co-editor of William F. Buckley’s National Review. Burnham also contributed a weekly foreign policy column to Buckley’s magazine and wrote a number of bestselling books on politics and international relations.

Burnham had started out with the radical left as one of Trotsky’s leading American disciples. But he broke with Marxism. Subsequently, he wrote The Managerial Revolution, predicting that the coming order would be a world-conquering managerial technocracy and run by a New Class of engineers, administrators and educators. These technocrats would wield power through the interpretation of cultural symbols, the manipulation of state-authorized mechanisms of mass organization, and economic redistribution.

Burnham’s Foreign Policy

Similar to Strausz-Hupé, Burnham believed liberalism is incapable of understanding the brutal Machiavellian realities of politics. Also similar to Strausz-Hupé, he borrowed his ideas from Europe. He wrote a book on political theory and practice, entitled The Machiavellians. In this book, he identified a group that had been influential in Europe but almost unknown in the United States. The Machiavellians included Gaetano Mosca, Georges Sorel, Robert Michels and Vilfredo Pareto. Burnham claimed their writings held the truth about politics and the preservation of political liberty.

He argued that all societies are ruled by oligarchs through force and fraud, and that cultural conventions, myth and rationality are all that holds them together. However, a scientific attitude toward society does not permit the sincere belief in the truth of the myths. Democracy itself was a myth designed and propagated by elites to sustain their rule under secular modernity. If the leaders are scientific, they must lie. Liberty requires hierarchical structures, cultural renewal and the primacy of patriotism, all of which were against the liberal consensus.

The Machiavellian World View

Burnham worked on a secret study commissioned by the Office of Strategic Services in 1944 to help prepare the US delegation to the Yalta Conference. In the resulting book, The Struggle for the World, he argued that the Soviet Union had become the first great Heartland power. Therefore, the only alternative to a Communist World Empire was an American Empire. The American Empire would be established through a network of hegemonic alliances and colonial and neocolonial relationships. This was Burham’s response to the revolutionary ideology and continuous expansion of the Soviet Union.

In place of appeasement, he advocated a policy of immediate confrontation. Containing Communism, and overthrowing Soviet client governments in Eastern Europe would be the goal. Intense political warfare, auxiliary military actions, and possibly full-scale war would be the method.

Machiavellianism in Vietnam

This debate extended to the Vietnam War. Burham attacked the ‘Kennan-de Gaulle-Morgenthau-Lippmann approach because it over-emphasized the nationalist dimension of the Cold War at the expense of what he believed was its more fundamental counter-revolutionary character. He said the realists’ analysis seemed plausible, but they failed to grasp the broader geopolitical and metaphysical consequences of a withdrawal–a communist takeover of the Asian continent. He admitted that entering the war may have been a strategic mistake, but it had become America’s ultimate test of will.

Burnham maintained a holistic approach to social theory even though he renounced Marxian theories of universal history. Like Strausz-Hupé, he saw the Cold War as geopolitical and metaphysical. He thought sacrifice was needed for survival, and America’s liberal philosophical and cultural commitments were not up to the task. He expanded on this idea in his book, The Suicide of the West.

Stefan Possony: Race, Intellect, and Global Order

Stefan Possony, also a collaborator of Strausz-Hupé, was also from Austria. He was involved in conservative foreign policy debates in the US for almost 50 years. He held research positions at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, the Psychological Warfare Department at the Office of Naval Intelligence, and the Pentagon’s Directorate of Intelligence. In addition he taught strategy and geopolitics at Georgetown. In 1961, he became Senior Fellow and Director of International Studies at the Hoover Institute at Stanford. Also similar to Strausz-Hupé, Possony served as a foreign policy advisor to Goldwater’s presidential campaign. Like Burham, he advocated an ‘offensive forward strategy’ in the Vietnam War. Possony became an advocate for President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative in the 1980s.

Possony’s Theory of Racial Hierarchies

Possony was also interested in racial hierarchy. Racial geopolitics was central to his vision of international order. He co-authored Geography of the Intellect with Nathaniel Weyl. In this work, the authors tried to demonstrate the racial hierarchy and geographic distribution of intellectual abilities and their implications for foreign policy. They argued that world power and historic progress depended on racially determined mental capacities and the ability of an elite to influence society’s direction. And they concluded that intelligence is directly connected to the comparative mental abilities of different races. The people with the largest amount of creative intellectual achievement since the Middle Ages are within the Western political orbit. Hence, the West’s geopolitical dominance.

However, Possony and Weyl argued that Western dominance was threatened by technological advancement and demographic dynamics. This process allowed the less able to out-reproduce the elites. They echoed Spengler with this argument.

As societies reach the peaks of civiization and material progress they face the threat of application of a pseudo-egalitarian ideology to political, social and economic life – in the interests of the immediate advantage of the masses who, for political reasons are told that if all men are equal in capacity, all should be equally rewarded. The resources of the society will be thus increasingly dedicated to the provision of pan et circenes (bread and circuses) – either in their Roman or modern form. Simultaneously, excellence is downgraded and mediocrity must fill the resulting gap. As the spiritual and material rewards of the creative element are whittled away, the yeast of the society is removed and stagnation results.

Page 283 – 284Selective Genetic Reproduction

Selective genetic reproduction via artificial insemination was proposed as a partial response. This followed Hermann J. Muller’s ‘positive eugenics’. Possony argued that through artificial insemination, a small minority of the female population could multiply the production of geniuses in the world.

Possony and Weyl also argued that America’s aid policies and support for decolonization were misguided. This was similar to arguments proposed by Burnham and Strausz-Hupé. They reasoned that such policies are based on the incorrect assumption that men, classes and races are equal in capacity, and that human resources can be increased by education. These policies have unleashed the forces of brutal race and class warfare in Africa and the Middle East. They also force the emigration and expulsion of the European elite. And the European elite is the only elite.

Treason of the Scholars

In addition to these classic tropes, these men argued that the West’s decline was partly due to the ‘treason of the scholars.’ In other words, treason of liberal intellectuals who are guilty of spreading specious egalitarian ideals. Such ideals sow envy, anxiety, dissent and disloyalty among the masses. The treasonous ‘pseudo-intelligentsia’ must be supplanted by a creative minority.

Gerhart Niemeyer

Gerhart Niemeyer was a native of Essen, Germany. Like Burnham, he began his career on the left as a student of the social democratic lawyer Hermann Heller. He emigrated to the United States in 1937, via Spain, and taught international law at Princeton and elsewhere before joining the State Department in 1950. He spent three years as a specialist on foreign affairs and United Nations policy. After two years as an analyst on the Council of Foreign Relations, he became a Professor of Government at Notre Dame University. He remained there for 40 years.

His 1941 book, Law Without Force, was part of a postwar attempt to relate international law to power politics. It was influenced by Hermann Heller’s conception of state sovereignty and by Niemeyer’s despair over ‘the politically naive legalism of the Weimar left’.

Criticism of International Law

Niemeyer believed modern international law was unrealistic by nature and that it was partly responsible for the unlawfulness of ‘international reality’. He claimed that during the nineteenth century, international law had been transformed by the rise of liberalism into a mere instrument for managing the common affairs of the bourgeoisie. It now served the ideal of an interdependent global society of profit-seeking individuals. Subsequently, the rise of authoritarianism had made legal norms obsolete. Since international order is established through law, the law must be renovated based on Niemeyer’s criteria.

The Influence of Eric Voegein, Buckley, Goldwater, and Traditionalism

Niemeyer was influenced by Eric Voegelin, and he became a Traditionalist during his time at Notre Dame University. For decades, he was a friend of William F. Buckley. He was considered an expert on Communist thought, Soviet politics, and foreign policy, and was commissioned by Congress to write The Communist Ideology. This work was circulated in 1959-60. Like Strausz-Hupé and Possony, he worked as a foreign policy advisor on the Goldwater campaign. Subsequently, he served as a member of the Republican National Committee’s task force on foreign policy from 1965 to 1968.

Metaphysical Meaning of the Cold War

Niemeyer believed that political modernity is a uniquely ‘ideocratic’ epoch where dominant ideologies strive for new certainties in order to remake the world. Voeglin called this ‘political gnosticism’. The result is a world dominated by ruthlessness, absolutism, and intolerance in which logical murders and logical crimes made the twentieth century one of the worst in human history.

These convictions led him to a radical vision of the Cold War. In his view, the Cold War became an explicitly conservative metaphysical phenomenon. Liberals failed to see that the Soviet Union was not simply a great power adversary but an implacable enemy drivin by gnostic desires of the ‘Communist mind’. He further argued that the Communist mind was a ‘nihilistic and pathological product of modernity’. So, it was natural for people to fear Liberalism as superficial, ignorant of people’s demonic possibilities, given to mistaken judgments of historical forces, and untrustworthy in its complacency.

Niemeyer believed the world is at a spiritual dead end. Political orders rest on a matrix of customs, habits, and prejudices underpinned by foundational myths. So, the solution is a mystical awakening that recognizes the importance of mystery and myth in political life.

What They Had in Common